Five score and one week ago, Geneva Hardman was killed on her way to school. Five days later, the confessed accused was convicted and sentenced to die. News of the killing, the trial, and the ensuing riot achieved national attention. As a result, correspondence from across the country (as well as locally) was directed to Geneva’s grieving family.

The family retained these letters over the decades that followed. Some were from relatives who had moved away and others were from complete strangers. One letter, in particular, stood out. It was written by Agnes Plummer of Providence, Rhode Island.

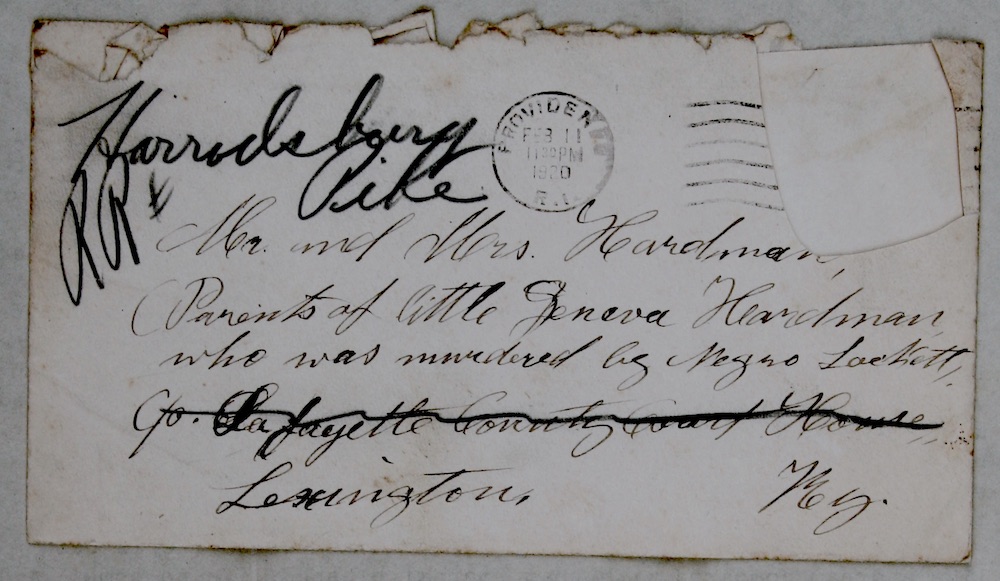

Ms. Plummer was a “friend unknown” to the Hardman family; she knew nothing of the family beyond that which she read in her newspaper. The envelope was addressed to: Mr. and Mrs. Hardman (Parents of little Geneva Hardman who was murdered by negro Lockett) c/o Lafayette County Court House, Lexington, Ky.

For those who have been following this centennial series, you will recall that Geneva’s father had died almost nine years earlier and that her mother had not remarried. Further, Lexington is located in Fayette (not Lafayette) County.

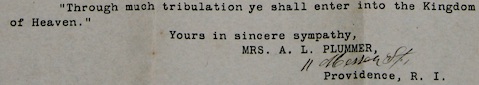

Inside the envelope, a typewritten letter encouraged “Mr. and Mrs. Hardman to go to “our Redeemer for consolation.” The religious prose in 69-year-old Agnes Plummer must have been a comfort to the Rhode Islander who herself was grieving from burying six of her own children.

Some of Plummer’s “heartfelt sympathy” was lost by her use of the typed form letter, which crossed out in pen any typewritten masculine identity of the victim. For example, a sentence from the letter from Plummer to Hardman read as follows: “And if you would but believe and be able to realize that if you could see your beloved son daughter in that supremely happy state of existence, you would not wish him her on the earth again,” where the italicized words were penciled in above the marked-out masculine terms.

This author’s assumption that the Plummer letter was a form letter was confirmed when I discovered an identical letter written eight years earlier included at length in Nita Gould’s book Remembering Ella about the 1912 murder of an 18-year-old woman in northwest Arkansas.

It was the only form letter in the mix. In The Murder of Geneva Hardman and Lexington’s Mob Riot of 1920, I’ve included several of the letters received by the family in the wake of Geneva’s murder. Her school and church also passed resolutions expressing their condolences to the family.

Whether from those who knew Geneva Hardman and her family, or whether from “unknown friends” who simply learned of the events that transpired from newspaper accounts, there was an outpouring of support expressed to Mrs. Hardman and family during their time of tragedy.

This post contains excerpts from Peter Brackney’s The Murder of Geneva Hardman and Lexington’s Mob Riot of 1920 (The History Press, Charleston, SC: 2020).

For more information about the book or to schedule an event with the author, click here.