Do you recognize this double decker?

Share your memories in the comments!

|

| Hart-Bradford House at Second & Mill Streets – Lexington, Ky. Photo: Library of Congress |

I was slightly incorrect on last week’s #ThrowbackThursday photo as I observed only two famous occupants. At least four are worthy of mention: Thomas Hart, John Bradford, John Hunt Morgan, and Laura Clay.

The property was accurately guessed quickly by Jason Sloan, the Historic Preservationist with the Blue Grass Trust. Jason had an unfair advantage, though, as the BGT was founded in the wake of the demolition of the photographed property.

The property was known as the Thomas Hart / John Bradford House, though I fully overlooked the first occupant.

Col. Thomas Hart was a veteran of the American Revolution and a Marylander. In the early months of 1794, Col. Hart sent letter to friends in Lexington to procure for him a house in Lexington. In an earlier letter to Gov. Blount of Tennessee, Hart wrote

You will be surprised to hear I am going to Kentucky. Mrs. Hart, who for eighteen years has opposed this measure, has now given her consent and so we go, an old fellow of 63 years of age seeking a new country to make a fortune in…

Hart had been both at Boonesborough and had been a principal in the Transylvania Company which, had it been successful, would have forever altered Kentucky’s lot. At the age of 63, Hart arrived in Lexington in June of 1794.

In the late 1790s, ca. 1798, Hart constructed for he and his family a home on the corner of Second and Mill Street. He owned the entire block – now bordered by Broadway, Short, Mill, and Church Streets – which he utilized for his many business ventures.

Hart may be best known for his son-in-law as his daughter, Lucretia, married Henry Clay. In fact, the nuptials occurred in this very house! As a gift to his son-in-law, Hart erected next to his own house a home for Lucretia and Henry. At the time, Clay practiced law across Mill Street.

Hart died in 1808 and after the house was sold to John Bradford.

|

| John Bradford Photo: U. of Kentucky |

John Bradford purchased the Hart home from Thomas Hart, Jr. for $5,000. Bradford had begun the Kentucke Gazette in 1787; it was the first newspaper in the Commonwealth. Herald-Leader columnist Tom Eblen described Bradford as “a Renaissance man of the early Western frontier” before creating a laundry list of endeavors in which Bradford found himself actively occupied: “land surveyor, Indian fighter, politician, moral philosopher, tavern owner, sheriff, civic host, community booster, postal service entrepreneur, real estate speculator, subdivision developer, mechanic and mathematician.”

The Gazette changed names in 1789 when it adopted what we now view as the conventional spelling of Kentucky. The change was precipitated by an official act of the Virginia legislature.

One cannot underestimate Bradford’s contributions to the region. He was the man “behind the scenes” accomplishing much and bringing Lexington with him. It is a question whether Lexington would have become the Athens of the West were it not for John Bradford.

On March 22, 1830, Bradford died at his home on the corner of Second and Mill Streets. His burial location is unknown, but there is some evidence from the early 20th century that the location was under the western wall of First Baptist Church (the site of Lexington’s first burying grounds). In 1926, the John Bradford Society dedicated and mounted a plaque on the Second Street side of the Hart-Bradford Home, which read:

This House Was the Home of

John Bradford

1749-1830

A Pioneer Settler of Lexington

First Printer of Kentucky

Co-Founder of The Kentucky Gazette

A Prominent, Public-Spirited and Useful Citizen.

The plaque is visible at the center of the photo above.

The Bruce family which followed the Bradford’s at 193 North Mill; here Rebecca Gratz Bruce was born three months after Bradford’s death. In 1848, Rebecca would go on to be married in this house to John Hunt Morgan and the couple lived here briefly for a time before the Civil War. Remarkably, their marriage and occupancy is only a footnote in the history of the property.

|

| Laura Clay Library of Congress |

Laura Clay, daughter of noted abolitionist Cassius Clay, removed here from White Hall in Madison County where she had been born. She founded the Kentucky Equal Rights Association and sought suffrage and equality for women.

It is interesting to note, however, she opposed the passage of the 19th Amendment on the grounds of states’ rights.

In 1920, Clay was a delegate from Kentucky at the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. The photo below is from the convention at which Clay become the first woman in either major political party to have her name placed in nomination for President of the United States.

|

| 1920 Democratic National Convention. Ms. Clay, far left, and the other Kentucky delegates. Photo from John Rhorer, whose grandfather wears the hat (r) |

Ms. Clay died in her home at the corner of Second and Mill Streets in 1941. She was 92.

In 1955, the Hart-Bradford-Clay home was razed in favor of a parking lot. The demolition did, however, prompt a group of preservation minded individuals to go about ensuring that the same fate did not befall the Hunt-Morgan House. The group, “The Foundation for the Preservation of Historic Lexington and Fayette County” expanded its mission and simplified name to today be known as the Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation. In 1958, Gratz Park was made Lexington’s first historic district; today there are fifteen.

193 North Mill Street remains only a parking lot; nothing has risen from her ashes. It can be said, however, that her demolition galvanized members of the community to the great task of preserving Lexington’s historic and cultural resources.

Sources:

Blue Grass Trust. Gratz Park Spreads. Brochure, available here.

Coleman, Jr., J. Winston. John Bradford and the Kentucky Gazette. Filson Quarterly, v. 34 1960, available here.

Dunn, Frank C. Old Houses of Lexington. Typescript, n.d. transcribed and available here.

Eblen, Tom. Essay: John Bradford, Kentucky’s Pioneer Journalist. 11 June 2013, available here.

Hudspeth, Susan. John Bradford: Pioneer Printer of Kentucky.

Kentucky Women in the Civil Rights Era. Laura Clay: Kentucky Suffragette, available here.

Pierces.org. Colonel Thomas Hart III, available here.

|

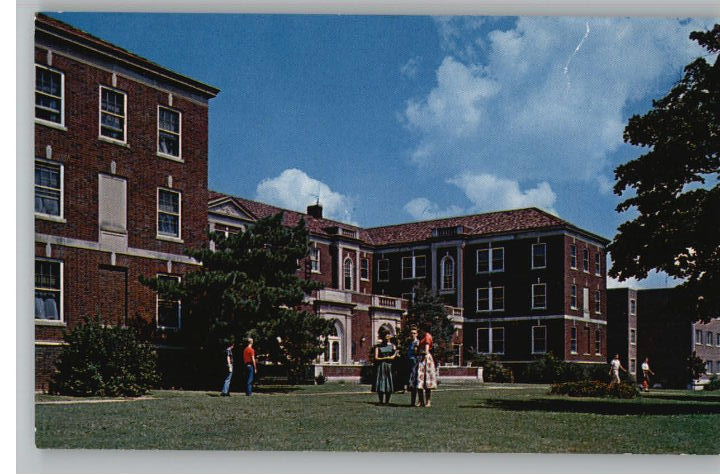

| Ordway Hall, ca. 1931 – Murray, Ky. Photo: Murray State University Special Collections & Archives, File No. RG002-11-39 |

|

| Entrance to Ordway Hall – Murray, Ky. Photo: Tripp Scott. |

The wrecking ball could be heard yesterday as it began the systematic demolition of Ordway Hall on the campus of Murray State University. According to a former MSU President Randy Dunn’s facilities update video, Ordway violated “current safety standards and has an overall weak structure thus threatening its integrity.”

Dunn cited a tight campus budget in arguing that the estimated renovation costs, in excess of $10 million, were too great for the University to bear.

So Murray State paid about $2 million to demolish a piece of its history.

The building was one of the oldest on Murray State’s central campus, though it falls just outside the boundaries of the National Register file on the Murray State campus.

|

| Postcard of Ordway Hall – Murray State University – Murray, Ky. Source: Billy’s Postcards |

Future plans for the site are not yet determined, but demolition efforts do include an attempt to preserve the front façade of the 1931 structure. Ordway Hall was named for G. P. Ordway who served on the University’s Board of Regents. A Republican, Ordway was an alternate at the Republican National Convention held in Kansas City, Missouri in 1928, during which California’ s Herbert Hoover was nominated for the Presidency.

Back in Calloway County, the contract for the building was awarded on April 10, 1930 to W.M. Hill & Son of Benton, Ky. Exclusive of furnishings, the total cost to construct was $106,765. It was originally used as a men’s dormitory when it opened in 1931, except the men were moved to Wells Hall and the female students moved in during World War II when naval units utilized the campus.

When the Board of Regents voted in December 2011 to approve demolition unless outside funds were made available to rehabilitate Ordway Hall, the vote was 9-1. The lone dissenting vote was from Marilyn Buchanon who remarked

I would like to say that this building does not belong to this board. It belongs to the citizens of Kentucky. It belongs to the alumni of this university who have studied here for the past several years, and it belongs to the students of the future who will share in a rich tradition we have enjoyed. It is a part of all of us, and when we destroy it, we destroy a part of ourselves.

Sources

Anderson, Meghan. Under Ordway: Plans for demolition begin, Murray State News. 29 April 2013, available online.

Teague, Hawkins. Ordway Hall to be torn down after 82 years, Murray Ledger & times. 15 July 2013, available online.

Teague, Hawkins. University Regents vote to raze Ordway Hall, Murray Ledger & Times. 10 December 2011, available online.

Woods, Ralph H. Murray State University: Fifty Years of Progress, 1922-1972. Pamphlet, 1973. Available online.

George Ella Lyon asks in her essay, “What has happened to our taste for differences?” As a society, we have come to expect uniformity as a sign of efficiency. The same menu at the same chain restaurant across the Interstate system is a sign of quality control.

The grocery store contains only a few varieties of tomatoes, though outside in home gardens and at farmers’ markets we can find heirloom varieties. Heirloom: as in, a relic of the past.

As a society, our ears seek that same uniform voice from those around us.

I must admit my prejudice, realized when a friend first opened her mouth announcing her hometown with three syllables: Inez (eye-neh-uz).

This educated woman conscientiously chose to retain both her voice and her local identity.

Aside from hearing our Appalachian brothers and sisters – and occasionally poking a little fun – we rarely consider the origin or background of the sounds.

Their is no singular Appalachian voice. Rather it is a collection of dialects spread over many parts of the country from upstate New York to rural Mississippi. In Talking Appalachian, published earlier this year by the University of Kentucky Press, editors Amy D. Clark and Nancy M. Hayward examine “The Englishes of Appalachia.”

The text is divided into two parts with the former being academic in style and the latter being a compendium of experiences and writings of famed writers like George Ella Lyon and Silas House. This second portion is a beautiful collection of the memories from home coupled with the sad reminders of discrimination.

The discrimination was not over skin color or sexual orientation or religion: it was caused because someone sounded different. Because someone embraced, as George Ella Lyon labeled it, their “voiceplace.”

The academic portion of the book would fascinate the linguist yet is too deep for the casual reader. Even so, its anecdotes caused a smile to creep onto my face as I thought of my wife’s Carter County family or the bluegrass gospel music I so enjoy.

Writing on “a-prefixing” were one of those moments in a chapter penned by Kirk Hazen, Jaime Flesher, and Erin Simmons as they examined a scene from The Golden Girls:

Dorothy: Ma, what are you doing?

Sophia: Getting ready. There’s a hurricane a-coming!

Dorothy: A-coming?

Sophia: Yes. People only use the a- if the really big storm is a-coming or a-brewing.

Dorothy: Look, Ma, I don’t mean to be a-criticizing you.

Sophia: Don’t you patronize me!

Dorothy: I’m not patronizing you. I’m a-mocking you.

That “a-prefixing” was used and is now used in literature to “highlight dramatic action” according to the authors. The authors note that the linguistic tool has been utilized for 500 years and was, in old, to indicate a present action. (Think Hank Williams, Sr.’, bluegrass gospel, Are you walking and a-talking with the Lord?)

Jeffrey Reaser highlights our education efforts – a one size fits all approach – to express concern that more of that local identity will be lost. It may not be the case, however, because standard broadcast English has been on the airwaves of Appalachia for a half-century while the people have largely retained their local voice.

Even so, it is the book generally that raises the question of whether our education system, or we as individuals, should put such an emphasis on one pronunciation over another. Katherine Sohn views her North Carolina voiceplace as being a source of language, of identity, and of power. I believe my friend felt the same way and I now commend her for not succumbing to the mores of a our uniform society.

In her poem Spell Check, Anne Shelby writes: “Now it wants to replace homeplace with just someplace. Is this the same spell that changed proud to poor, turned minnows into memories?”

In all our support of “buy local” we have often failed to support our local identity. Talking Appalachian reminds us to also support a person’s voice, identity, and community.

Disclaimer: The University Press of Kentucky provided the author with a courtesy review copy of the book here reviewed. The amazon.com link to the reviewed book is part of an affiliate agreement between the author and amazon.com.

|

| Big Ass Fans’ suggestion for corporation sponsorship of Rupp Arena (Source: Facebook) |

Mayor Jim Gray and Gov. Steve Beshear announced whose been hired to reinvent Rupp Arena with a little talk of how to pay for it, including possible naming rights. #FreeRupp [BizLex]

A tasty bourbon, Angel’s Envy, is opening its ditillery on Louisville’s East Main Street. [Governor’s PR]

Yet another version of the plans for Centrepointe have been approved. [Herald-Leader]

Perryville Battlefield named one of ten best Civil War sites in the country [Advocate Messenger]

UK’s Markey Cancer Center becomes a designated National Cancer Institute [Courier-Journal]

Richmond’s Terry Staggs uncovered a 2.95 carat diamond at Crater of Diamonds State Park in Arkansas. Over 75,000 diamonds have been uncovered at the site – about two per daily, far more than the prize gem found in Russell County in 1889.[KARK]

“I know not what course others may take; but as for me Give me Liberty, or give me Death!”

Patrick Henry’s famous oratory has been a call to freedom since he uttered those words before the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1775. Henry would go on to serve as the governor of Virginia from 1784 to 1786.

During this time, he signed a “perpetual and irrevocable” charter for the operation of a ferry boat in favor of John Craig. The ferry would cross the Kentucky River between Fayette and Madison Counties near the mouth of Tate’s Creek.

In 1798, Jessamine County was created from Fayette County with a portion of the boundary being along Tates Creek road to the Kentucky River. The General Assembly clarified the boundary in 1868, so that it would “run with the center of the said turnpike road leading from Lexington to the Kentucky River.”

It can thus be said that one headed southbound on the ferry departs from Jessamine, but those arriving on a northbound trip would arrive in Fayette.

From either direction, passengers on the ferry might pick up on the historical cues flying overhead. The vessel, aptly named the John Craig after the first ferry operator, carries four flags. The American, the POW-MIA and the Kentucky flags wave alongside the flag of Virginia under whose charter Valley View remains operational.

Few passengers in the 350 vehicles ferried daily probably consider the history of the ferry. For commuters, it is simply a vital shortcut between Richmond and Lexington or Nicholasville. For the tourists who often travel the ferry, the focus is on the nostalgic crossing itself.

Federal regulations imposed in 2006, however, are making it harder for the oldest continually operated enterprise in Kentucky to continue, since the operator must be a captain licensed with the United States Coast Guard.

Licensure can take four to six months and cost about $2,000. This makes it difficult to find a replacement captain when one resigns.

The John Craig has no steering capability and is tethered to overhead guide cables which are used to maneuver the vessel across the 500-foot stretch of river. Valley View isn’t the Staten Island Ferry or one of those crossing Washington state’s Puget Sound.

Yet it is snared into the bureaucratic red tape designed for these large ferries which sail on open waters. The regulations are a one-size-fits-all misfit threatening the Valley View Ferry’s own existence.

And while it seems that the Valley View Ferry Authority has secured a new captain which will, in due time, allow a return to normal hours of operation, the remaining existence of these federal regulations remain as a long-term threat.

That’s why U.S. Rep. Andy Barr (R-Lexington) introduced H.R. 2570, the Valley View Ferry Preservation Act of 2013, exempting the John Craig from Coast Guard licensure requirements.

The bill requires Kentucky to establish licensing requirements sufficient to protect ferry passengers.

In other words, the Preservation Act simply returns regulatory authority over the Valley View Ferry to the state.

Certainly, Patrick Henry would have been pleased with the Preservation Act. He was an ardent supporter of state’s rights who even declined to attend the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Henry feared that the federal government would become its own monarchy leaving little room for the individual States.

Allowing Kentucky to license the John Craig, while still leaving the vessel open to Coast Guard inspection, is a common sense solution critical to keeping America’s third oldest ferry operation afloat long into the future.

This column originally appeared in the Jessamine Journal.

It should not be republished without permission.

This home was intimately linked with two important individuals. During the occupancy of the latter, a plaque was mounted on the side of the house (nearly centered on the above photo) honoring the former.

After the dust had settled from the wrecking ball’s demolition of the landmark, private and public efforts began to protect Lexington’s historical resources. You are looking at the birthplace of Lexington’s historic preservation efforts.

But what are you looking at? And who were the two individuals alluded to above?

UPDATE: Read the history of this house and the answers to the questions asked by clicking here.

|

| Sayre School – Lexington, Ky. (R: David A. Sayre, headmaster’s office, Spartans colored stairs) |

David A. Sayre was a wealth silversmith from New Jersey who arrived in Lexington in 1811. By the end of the following decade, he had completely abandoned the trade in favor of commercial banking which had become a staple of the economy. With success, he quickly became one of Lexington’s most affluent denizens.

With his success, he contributed greatly to a number of philanthropic efforts. On November 1, 1854, Sayre founded the Transylvania Female Academy. Within a year, the school was renamed for its founder and benefactor as the Sayre Female Institute. The school began to admit boys in 1876 and finally dropping the gender-specific name in 1942.

During almost this entire history, Sayre School has operated at the same location: 194 North Limestone, now affectionately referred to as “Old Sayre.” (That brief interim as the Transylvania Female Academy found the school seated at the northwest corner of Church and Mill Streets.)

Old Sayre was constructed in 1846 as a two story, three-bay Greek Revival designed by local architect Thomas Lewinski as the home of Edward P. Johnson. Johnson lived here until 1855 when he sold the property to Sayre. By the end of the decade, two additional floors had been added to Old Sayre with the alterations being designed by architect John McMurtry.

|

| View of downtown Lexington from atop the cupola of Old Sayre. |

With the alterations, Old Sayre has assumed features of the Italianate style. On all four floors, the windows in the three bays are triple-section with the garret’s central window featuring a palladium window. Leading up to Old Sayre’s central architectural feature are a narrow set of stairs painted yellow and blue – the school colors. That signature feature is the square cupola topping Old Sayre, also having three windows on each side.

Given Sayre’s location just north of the downtown commercial district, the cupola offers sweeping views of downtown.

The property is seated on what was once Outlot No. 11 in the earliest of Lexington’s plans laid out in 1791. On this five acre tract and in the footprint of Old Sayre, Colonel George Nicholas constructed his home. Nicholas was, among other accolades and accomplishments, a prominent lawyer, Revolutionary War veteran, father of Kentucky’s Constitution, and the first attorney general of Kentucky. (Read more about Col. Nicholas here.)

Nicholas died in 1799 and is buried in the Old Episcopal Burying Grounds, the property was sold in 1806 to Thomas Hart, Jr. “who had a rope walk on the rear of the property.” (It is questionable whether the rope walk would today be considered an amusement ride and not permitted under present zoning law.) Hart’s family sold the land to Johnson who demolished the Nicholas home in favor of the two-story, supra.

David Sayre sought the formation of the school to provide an education of the “widest range and highest order.” Having survived through both the Civil War and the Great Depression, Sayre continues to provide such an education to her pupils.

Additional photos of the Sayre School deTour are available on flickr.

Sources: Lexington: Heart of the Bluegrass; NRHP; Sayre School

The Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation hosts a monthly deTour for young professionals (and the young-at-heart). The group meets on the first Wednesday of each month at 5:30 p.m. Learn more details about this exciting group on Facebook! You can also see Kaintuckeean write-ups on previous deTours by clicking here.

|

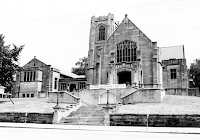

| The First Baptist Church – Lexington, Ky. |

Across Main Street from Rupp Arena, fifty stone steps climb over five landings to reach the sanctuary entrance of the circa 1913 First Baptist Church. The impressive structure is a Lexington landmark in part because of its prominent Main Street location and in part because of its architectural grandeur. The massive clock tower and red tile roof mark this iconic location.

Three former Baptist churches occupied the site, as did Lexington’s earliest burying ground. In fact, it was here that King Solomon buried the dead from the 1833 cholera epidemic. A decade and a half later, most of the bodies were relocated to the newly organized Lexington Cemetery.

Two of the old Baptist churches burned on the site, while the third was simply outgrown. When the extant structure was erected at a cost of approximately $125,000, it was built of Bedford limestone (Indiana) in the Collegiate Gothic style. Though the style is not often displayed in Lexington, it is commonly seen at the Ivy Leagues schools and at universities across the country.

|

| First Baptist Church; ca. 1975 (Source: NRHP) |

It is an impressive architectural style, made ecclesiastical at First Baptist through the repeated use of the quatrefoil, cross and other religious symbols in the exterior’s decorative stonework.

Entrance to the sanctuary is through a deeply recessed bay which had been closed in recent years because of structural concerns. Work on maintaining First Baptist has been a struggle as what was once one of the South’s largest Baptist congregations has drastically dwindled in number. With limited attendance comes limited tithe and offering, and the church building suffers.

All is not lost, however, as a handful of congregations now pool resources to call the First Baptist Church home. Each attempts to do its part in maintaining this magnificent piece of history.

Originally meeting in the homes of members as the Town Fork (or Town Branch) Baptist Church, it associated with the Elkhorn Association on August 15, 1786. Lewis Craig (brother to Elijah Craig) was involved in the establishment of Town Branch giving to First Baptist a hand on the legacy of the Traveling Church.

Rev. John Gano was called in 1789 to the newly erected meetinghouse on the site. He had been a chaplain in the Continental Army having served throughout the long winter at Valley Forge.

A division arose in the church in 1826 when the influence of Alexander Campbell and the Restoration Movement brought Dr. James Fishback to introduce a resolution to change the church from Baptist to “Church of Christ.” The resolution was lost, so Fishback and his supporters departed First Baptist to organize the “Church of Christ on Mill Street” of which Central Christian Church is the eventual, albeit indirect descendent.

Inside, the first time visitor is overcome by the enormity of the cruciform shaped sanctuary. Anchored at front by pulpit and a choir balcony that also features an impressive pipe organ, the 1500-seat sanctuary features three additional balconies so that there is one on each wall. The pews and brass cluster chandeliers, all original.

It is, however, the “wide-grained chestnut timberwork over-arching the auditorium” that takes one’s breath away. Corbels at the base of each three-foot thick rib feature “intricately carved angels” while “horizontal bands of acanthus, leaves and acorns” adorn panelling above the pulpit.

And in case one is not sufficiently taken aback, five large stain-glass windows adorn. The space is one most Holy, Holy, Holy.

I visited First Baptist during a concert by the Lexington Area Music Alliance, LAMA. The concert was profiled yesterday and is available by clicking here.

Additional photographs of First Baptist Church and the LAMA concert are available on flickr.

Sources: Baptist History Homepage; Mickey Anders; NRHP (Historic Western Suburb); Historic Western Suburb NA; Tom Eblen

|

| Patrick McNeese Band (upper right); Chris Weiss (lower left) |

Last year, Lexington experienced her hottest Independence Day on record. This year’s holiday was hardly 99 degrees – instead the constant rain kept it a wee bit chilly.

LAMA is an origination committed to the support and economic vibrancy of local musicians. The artists performing were as spectacular as the venue.

The Patrick McNeese Band had a great sound. Easy listening with a jazzy edge and a bite of Bluegrass. McNeese writes the band’s music while playing the guitar and providing vocal. Other band members include Maggie Lander (vocal/violin), Tom Martin (ivories), Scott Stoess (bass), and Tripp Bratton (percussion).

|

| Cave Run Lake – Rowan Co., Ky. |

Solo guitarist Chris Weiss’ music has many of those same coffee shop, easy listening sounds affected by the regional influences of Appalachia. Basically, my kind of music. One song in particular I really enjoyed. Chris said he wrote it while on a boat on Cave Run Lake. While he played, I pulled up this post on Cave Run Lake and imagined myself their again as I looked at the beautiful Rowan County scenery. It took me back.

The whole concert was awesome. In fact, I came to take advantage of the opportunity to visit First Baptist Church. Yet, I remained for the two hour concert.

Great music and I hope the ‘Music in the Church’ series is a big hit.

The venue for the concert, First Baptist Church in Lexington, is profiled here.