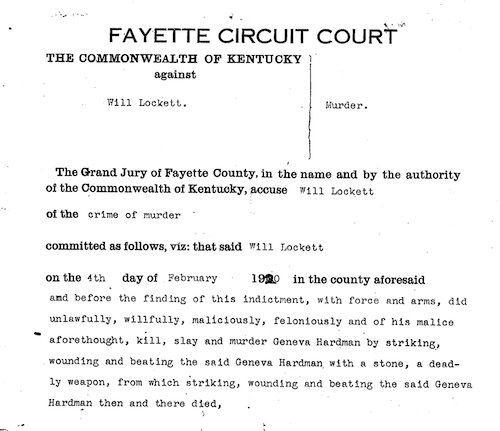

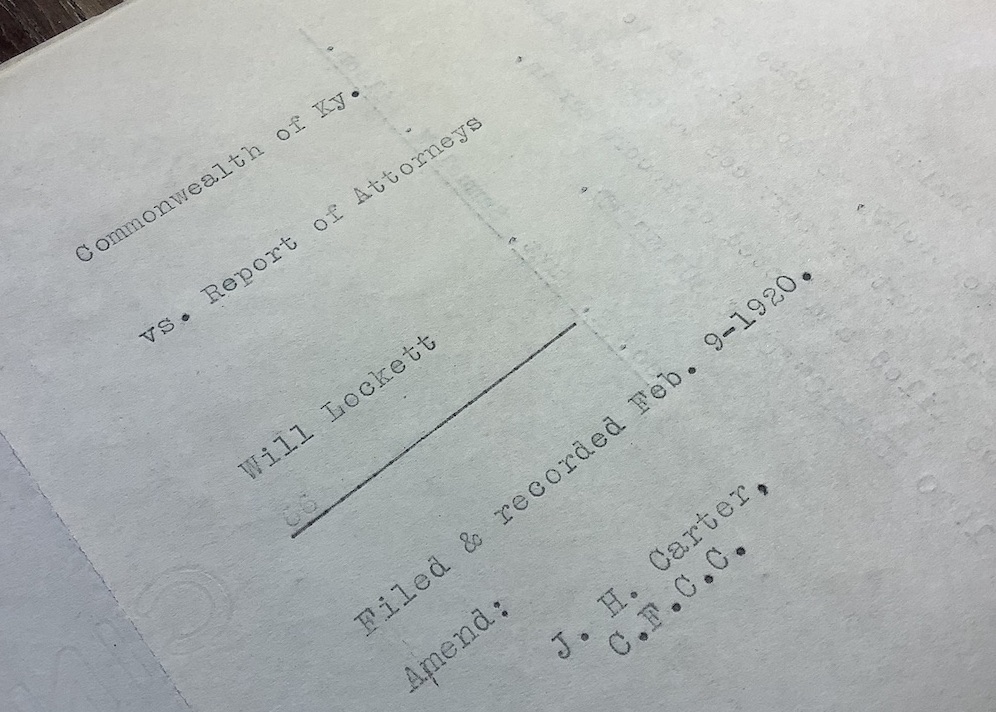

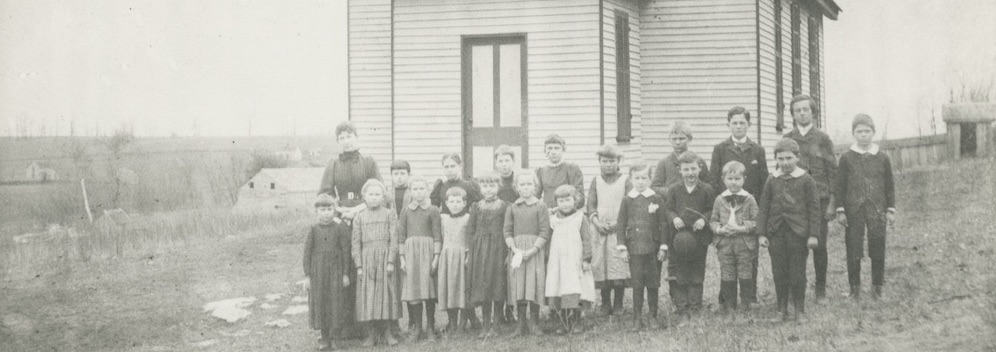

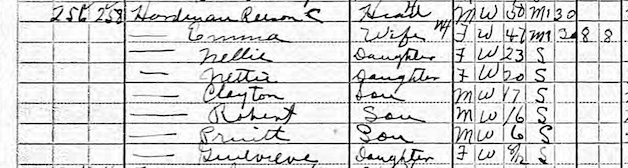

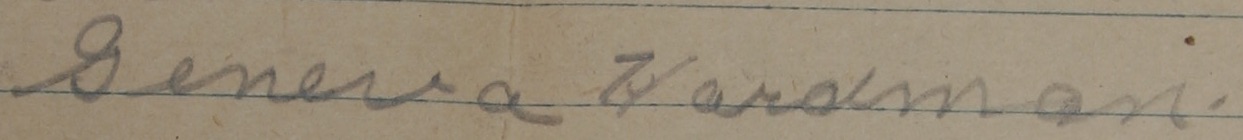

On the eve of the trial of Will Lockett, tensions in Lexington were strong. Lockett, accused in the death of Geneva Hardman was awaiting trial at the state reformatory in Frankfort. While many wanted Lockett hung, others called for calm.

A brother’s cry for peace

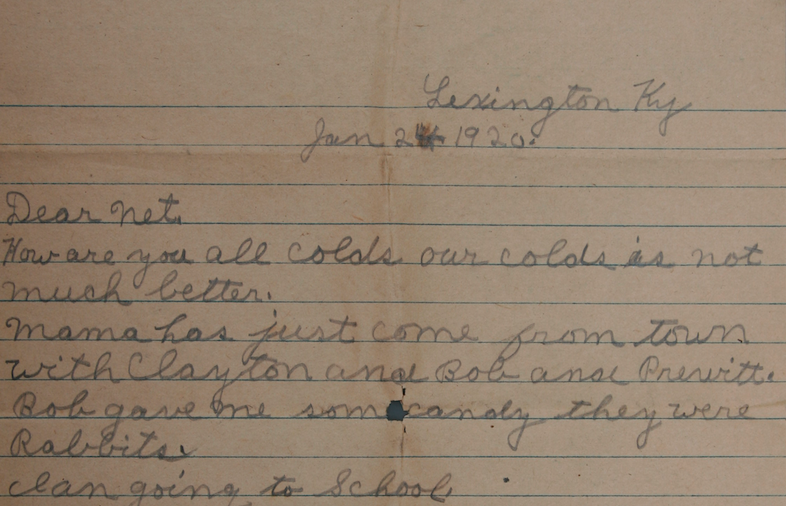

The most notable plea for a peaceful trial came from Tupper Hardman, the brother of the slain child. As reported in both of Lexington’s newspaper Sunday editions on February 8, 1920, Mr. Hardman offered this statement on Saturday, February 7:

As a brother of Geneva Hardman, who was murdered by Will Lockett, and as a representative of her family, I request all of our friends and those who sympathize with us not to indulge in any violence or create any disturbance when Lockett is brought here for trial. The authorities have acted promptly, the man is under arrest, he has been indicted promptly and his trial fixed for next Monday.

There is no doubt of his guilt and he has confessed to it, and I feel surethat a prompt and speedy trial will take place and that any jury empaneled will find him guilty and punish him adequately for the horrible crime he has committed.

The precipitation of a battle or conflict between the authorities protecting the man and citizens who are justly indignant over the crime would necessarily result in many deaths and probably the killing of innocent bystanders who are taking no part in the conflict.

I would hate to see the life of any other person endangered or lost as the result of violence by reason of a conflict over a brute like this and I, therefore, urge all citizens, for the good name of the county and in the interest of law and order, to do nothing to interfere with the orderly processes of the law, because I am confident that prompt and exact justice will be done, and that punishment commensurate with the crime will be meted out to this man.

From the mouth of one so close to the victim, the statement by Tupper Hardman was lauded locally and nationally for its eloquence and “true Christian spirit.”

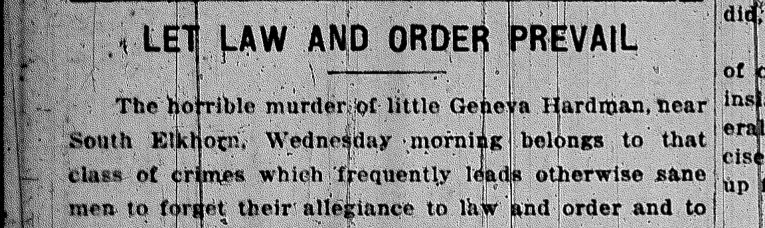

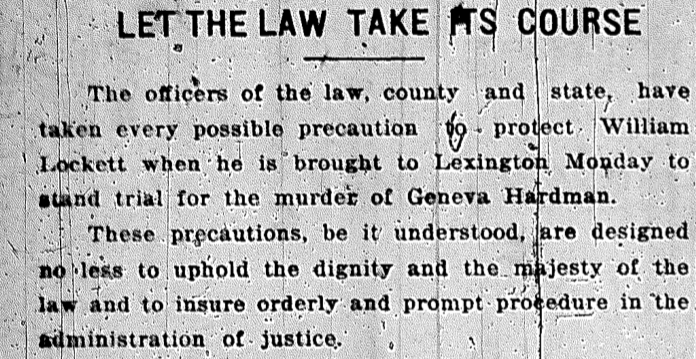

In a similar vein, the Lexington Leader wrote an op-ed under the headline “Let the Law Take Its Course.”

As would be discovered the following morning during the trial, not all had the same sentiment.

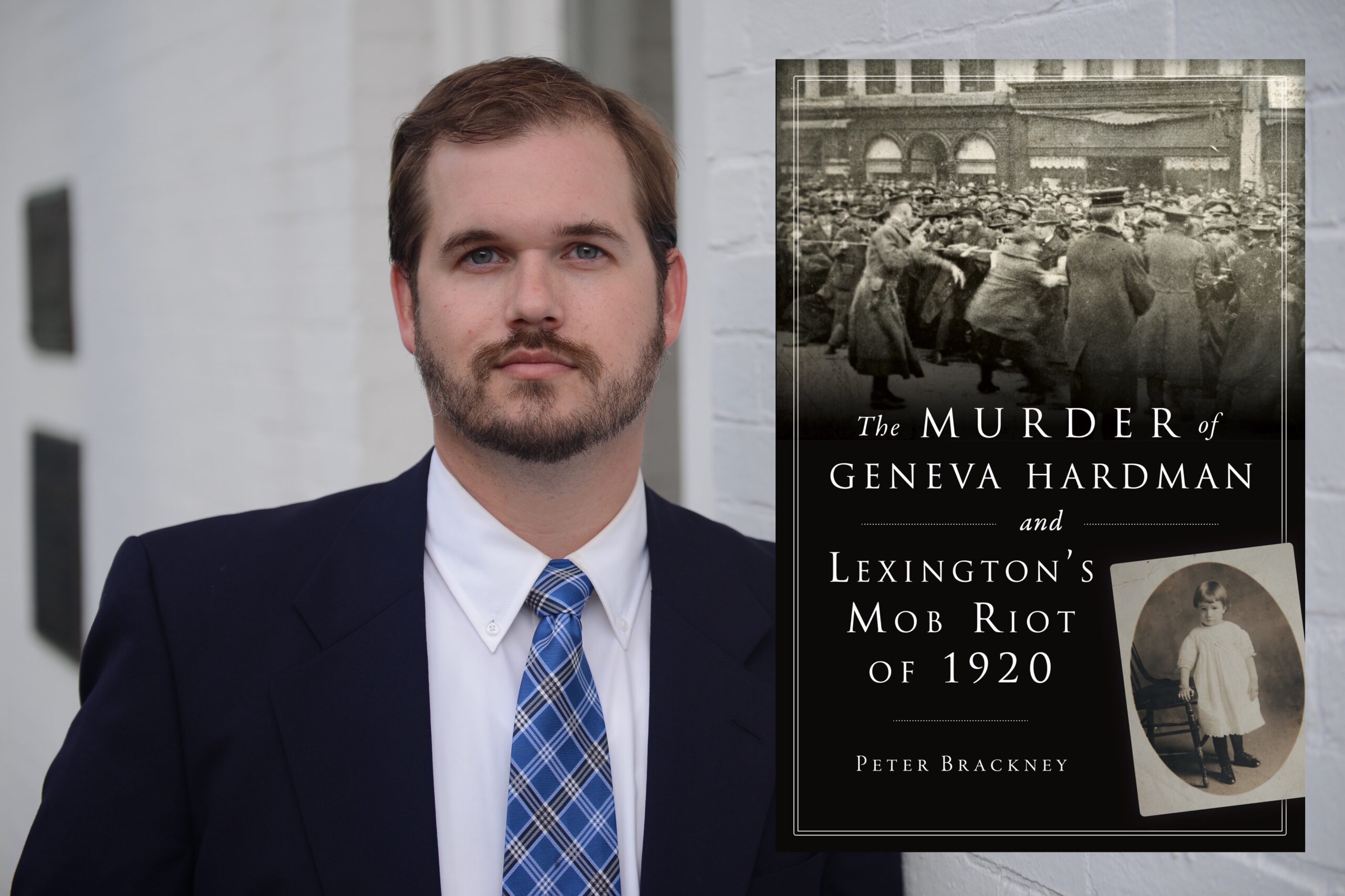

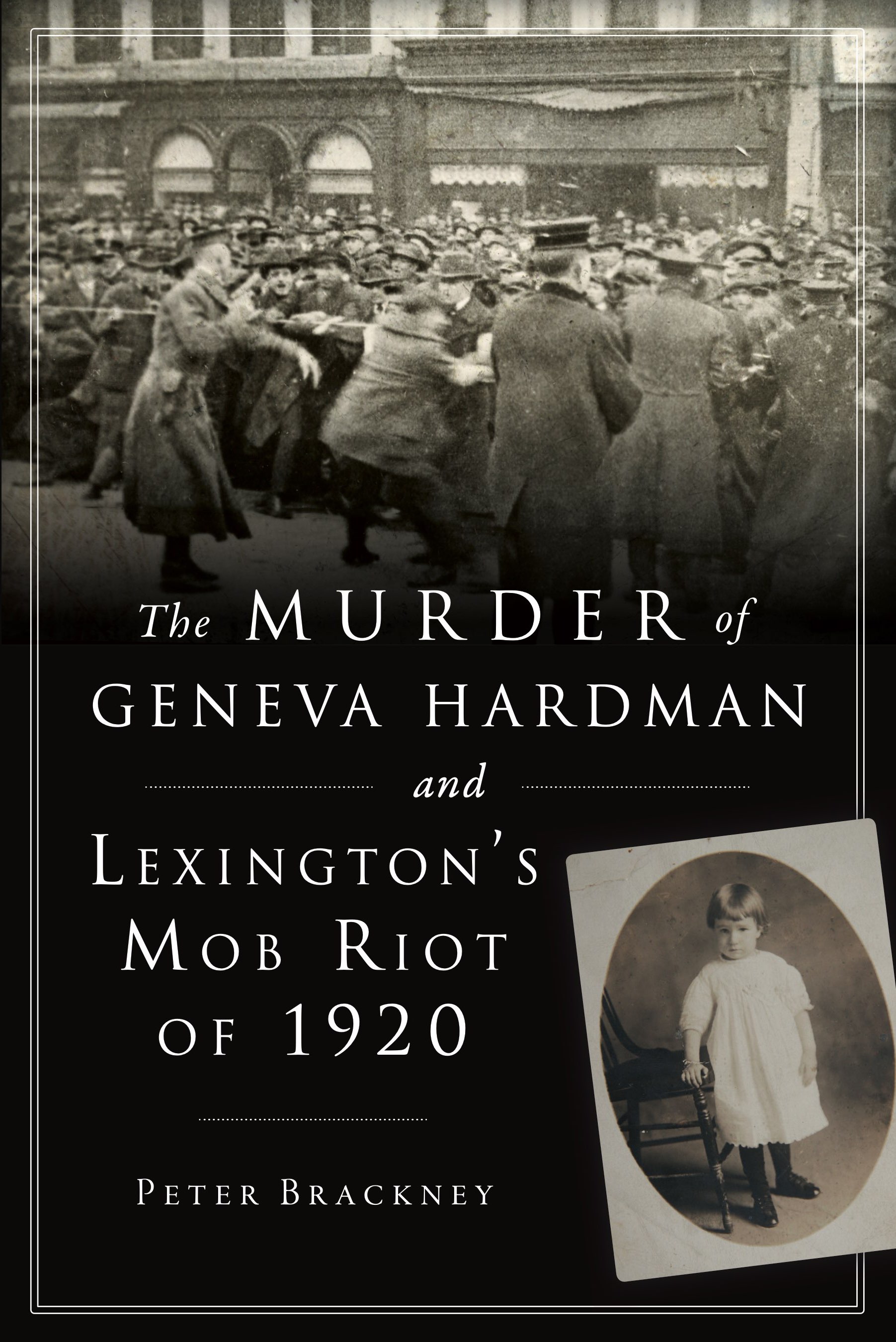

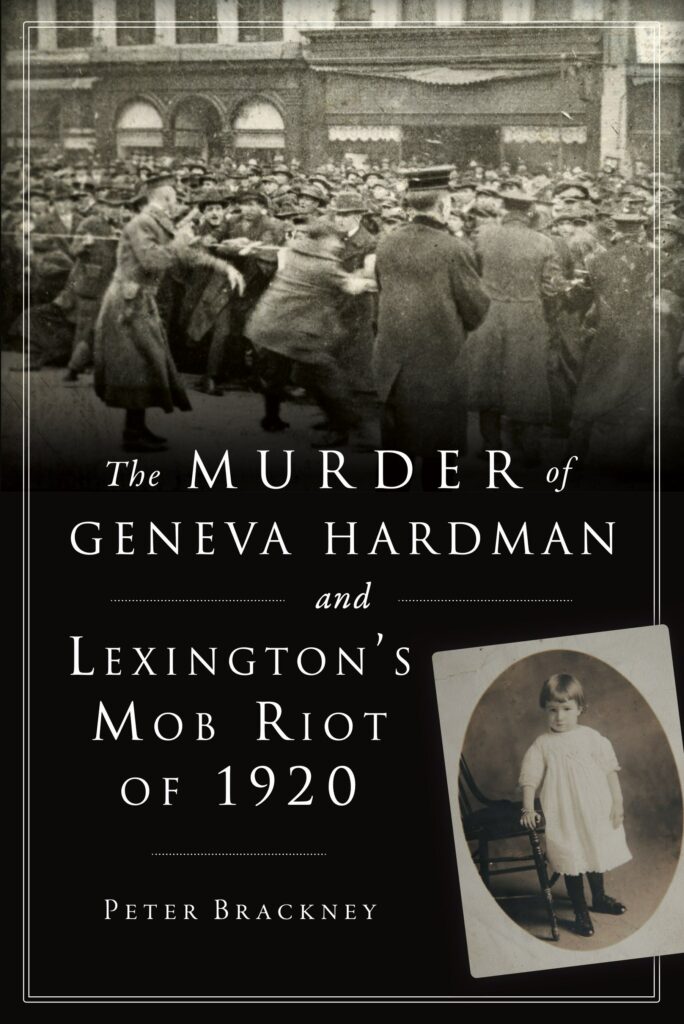

This post contains excerpts from Peter Brackney’s The Murder of Geneva Hardman and Lexington’s Mob Riot of 1920 (The History Press, Charleston, SC: 2020).

For more information about the book or to schedule an event with the author, click here.