The native limestone façade of the Church of the Advent features a tower with pyramidal roof, steep gable-fronted nave with verge boards inspired by tracery, buttresses, triple lancet windows enclosed by stone pointed arch hood mold. This romantic Gothic Revival church, one of my favorites inspired me to look into a whole group of mid-nineteenth century churches associated with Kentucky’s first Episcopalian Bishop Benjamin Bosworth Smith.

The Church of the Advent was the first Gothic Revival Episcopal church built of stone in Kentucky. It was built beginning in 1855 when the cornerstone was laid and the tower was completed in spring 1860. The plan was said to be taken from a model made by Bishop Smith of St. Giles Parish Church at Stoke-Poges in England. St. Giles was famous as the setting for the poem, Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard by Thomas Gray. A comparison of the Church of the Advent with the actual St. Giles shows, however,t only faint similarities.

The Church of the Advent was one of a number of Gothic Revival Episcopal Churches built through the influence Kentucky’s first Episcopal Bishop, the Right Reverend Benjamin Bosworth Smith. The Gothic style was felt to be the only proper style for a church by Anglicans who were part of the Ecclesiological Movement or the Oxford Movement. This influenced Episcopalians in America to favor the Gothic Revival style for church-building. The style of churches built after Bishop Smith’s model was patterned after the Early English Gothic style of the 12th and 13th centuries which was simpler than the later phases of Gothic, the Perpendicular Gothic and Decorated Gothic styles. This made it adaptable to the small churches designed for Kentucky towns. These churches are reminiscent of English country parish churches, particularly those built of native limestone.

|

|

The tower features a Tudor arch doorway with a shouldered hood mold. A Tudor arch is a flattened pointed arch. The stonework for the lower part of the tower is uncoursed stone while the upper part of the tower completed later has the stone laid in courses. Buttresses support outer corners, tall slender single lancet windows are on each face of the upper tower and the cornice has stone corbels under a pyramidal roof.

The Episcopal congregation in Cynthiana was formed in 1835 by N. N. Cowgill, a layman who later was ordained by Bishop Smith in 1838. For several years the congregation did not have its own church meeting and held services in the Methodist, Presbyterian and Christian churches as well as in the courthouse. Two more priests would serve the congregation before Reverend Carter Page in 1850 who would be pastor during the construction of the church. The church cost $6,500 dollars to construct. The lot was purchased by Dr. George H. Perrin who paid for $5,500 of the cost with the remaining$1000 donated by William Thompson. Once the tower was completed the church was consecrated on May 19, 1860 by the Right Reverend (Bishop) Benjamin Bosworth Smith.

During the Civil War, the church would be used for a hospital for the wounded soldiers from the Battle of Cynthiana fought on June 11th and 12th, 1864.

The side porch of the Church of the Advent with trefoil motifs in the brackets and verge boards. Note how acute the angle of the gable is. In medieval Gothic churches the porch was usually enclosed or partly enclosed.

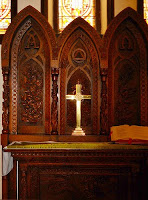

Interior of the Church of the Advent

The first thing you notice when you enter the church is the open beam ceiling featuring cross beams supported by arched beams springing from the side walls. Centered on the front and back walls are the triple lancet windows. On each side of the windows on the back wall are the Decalogue (Ten Commandments) and Apostle’s Creed, a common practice in 18th century Anglican churches of Virginia. The Apostle’s Creed uses an early version of the creed from the 1661 Book of Common Prayer rather than that from the 1789 Book of Common Prayer that was commonly used at the time.

The first thing you notice when you enter the church is the open beam ceiling featuring cross beams supported by arched beams springing from the side walls. Centered on the front and back walls are the triple lancet windows. On each side of the windows on the back wall are the Decalogue (Ten Commandments) and Apostle’s Creed, a common practice in 18th century Anglican churches of Virginia. The Apostle’s Creed uses an early version of the creed from the 1661 Book of Common Prayer rather than that from the 1789 Book of Common Prayer that was commonly used at the time.

An historic pump organ made in 1881 by H. Pilcher and Sons of Louisville is in the transept recess on the right. The organ was electrified in the 1950s.

The church had some minor redecoration in 1899 which included raising the chancel to a platform and adding a wood and cast iron railing separating the chancel from the nave. Lucy “Lutie” Tebbs and several other ladies carved the wood altarpiece and presented it to the church. It is said that she exhibited a large carved wooden pedestal at the Chicago World’s Fair.

The interior window openings are splayed and have original clear diamond-shaped panes. Lancet windows in the Early English Gothic style were usually in pairs or groups of threes. The wainscoting added in 1899 probably was unpainted in natural wood. The original pews have a jigsaw trefoil motif as finials on the top of each end.

I had a wonderful visit to Church of the Advent thanks to B. T. Darnell, Senior Warden. Besides the church stories she shared, she had fascinating stories to tell of her own property which was the site of Ruddle’s Station and the 1780 siege and massacre of settlers there by Captain Henry Byrd and his British and Indian troops during the American Revolution.

I hope to visit the other churches built during Bishop Smith’s tenure and report on them because they are each wonderful romantic churches. These include Holy Trinity Church, Georgetown (stone); St. Philip’s Church, Harrodsburg; Church of the Ascension, Frankfort; St. Paul’s Church, Shelbyville; St Paul’s Church, Pewee Valley (stone); St. Paul’s, Newport (stone). My next visit is to Holy Trinity Church in Georgetown.