Sorry, readers. No new posts this week; too busy to write. For now, enjoy this ‘live shot’ from Nicholasville Rd just north of Waveland Museum Lane.

Category: Uncategorized

No Destination: Diamonds!

One diamond was found in Kentucky (Russell County; though some poor quality diamonds were later discovered in the 1960s in Elliott County); it is thought to have been brought here during one of the glacial periods. The 0.776 carat diamond was purchased from the discoverer for $20 by a Louisville jeweler and the gem now is on display at the Smithsonian.

The events of the discovery were described in The American Journal of Science (vol. 28, no. 223-228 dated 1889):

To be sure, it is an interesting antecdote in Kentucky’s history. And, as my wife would say, “diamonds are a girl’s best friend.”

No Destination: Evangelist Dewey Cooper

If you have spent any time driving on Kentucky’s back roads, you have most likely seen a sign erected by Evangelist Dewey Cooper.

The signs are all the same: “Warning: Jesus Is Coming, Are You Ready?” and “Be Prepared: Jesus is Coming” they read with their red, white and blue colors.

According to a 2007 article, Cooper began erecting these signs throughout Kentucky in 1997. Although my first introduction to a Dewey Cooper sign was in Garrard County (US 27, just south of the Kentucky River), I couldn’t resist photographing this Russell County sign.

The community has its own religious/patriotic name: Freedom, Kentucky. It is the junction of US-127 and KY-55. According to the article, this is one of 31 of these signs erected by Cooper.

Dewey Cooper is an evangelist to 40 churches in the West Union United Baptist Association. The United Baptists have a long history in the United States and are the forerunners to today’s better-known Southern Baptists. Interestingly, it was originally those of faith – and particularly the United Baptists – who encouraged and promoted a strong separation between church and state.

No Destination: Jamestown

Although Russell Springs is the largest city in Russell County, Jamestown is the county seat. Originally named Jacksonville (after President Andrew Jackson), the area was renamed to honor James Wooldridge who had given the land for the town. The renaming of the community was actually prompted for political reasons; those opposed to Jackson came into power in the area around 1826.

Two Civil War skirmishes occurred near this sleepy community, a community that grew in popularity (particularly in the summer months) after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed Lake Cumberland in 1952. [Simultaneously, the population of Russell County dropped 19.3% between the 1950 and 1960 census.]

Jamestown’s city center is well-designed. A large town square finds the old (1978) courthouse in one corner, which is complemented on its opposite corner by the new judicial center (under construction). The other two corners have a number of businesses, including cafes, antique stores and other small-town essentials. The northwest corner is pictured above. In the center of the square is a large American flag under which a Doughboy stands as a memorial to the soldiers who served our nation. All of which begs the question: How many Doughboys stand on the “lawns” of Kentucky courthouses? (Casey and Carter Counties, among others, come to mind…)

Campbell County Courthouse REDUX – Newport, Ky.

So if there is anyone out there that pays attention to these posts, you might remember that I have had the Campbell County Courthouse on here before…but it wasn’t in Newport.

So looking back, I was pretty tired when I photographed the Courthouse in Alexandria. And that town is still terribly depressing. But I should have remembered the courthouse picture above, which I have passed numerous times in Newport and thought that something must be amiss here.

So here’s the deal. According to an article by Jim Reis that has been published on Rootsweb, the county seat was moved to Newport in 1797. The land for this courthouse was given by James Taylor, the founder of Newport. The first courthouse was built in 1815. Now, some people wanted the county seat to be closer to the center of the county, so it was moved to a small rural community called Visalia. Visalia was apparently in the middle of nowhere, so the seat was moved back to Newport, where it remained until 1840. That was until Kenton County was carved out of Campbell County, and the legislature decided to make another move to the center of the county, establishing the county seat in Alexandria.

As Reis says “[t]he transition from Newport to Alexandria wasn’t smooth.” It actually took a court order and a visit from the sheriff to get the county clerk to go to Alexandria.

I know there are many who wonder why Kentucky has so many counties. The story of why there is still a courthouse in Newport is the perfect answer to that question. In 1883, Newport lobbied the legislature for an exception to the state law that required county business to only be conducted in the county seat. A special law was created, creating the Newport Court House District, which allowed for Campbell County business to be conducted in Newport. However, as was clarified by a recent court decision, Newport is NOT a county seat. County business is just conducted there.

Anyway, the above courthouse is where county business is conducted in Campbell County. I had to go to a hearing in this courthouse, and there is a great deal of construction going on behind and in front of the building. I am a big fan of this building, as I think it’s a striking building in a community that I love. I’ve always been a big fan of Newport, both for its recent revitalization, and for its seedy history as a den of sin.

walkLEX: The Veep’s Final Flight

Again, thanks to Jamie Millard of the Lexington History Museum for documenting the move of General (CSA) and Vice President (USA) John C. Breckinridge (or, at least the statue of him being relocated within Lexington’s Cheapside Park):

No Destination: Russell Springs

This community – Russell County’s largest – was known as Big Boiling Springs when it was founded, though the local post office (est. 1855) postmarked letters as being from Kimble, Ky. It was not until 1901 that the town was named Russell Springs.

I drove through quickly; the only site I was able to see was a historic marker in a small park – Chalybeate Springs:

A health resort long known as Big Boiling Springs, operated before 1850 by family of Sam Patterson, among the earliest settlers. Log cabins (12) called Long Row were built for guests who came here for amusement, pleasure, and the medicinal iron and sulphur water. In 1898, large hotel built which burned in 1942. The spring has been capped for use as a well. [Marker 1233]

Unfamiliar with the term ‘Chalybeate’ I inquired further. The term simply refers to mineral spring waters with heavy iron deposits. Derived from the latin word for steel, “chalybs,” the most famous chalybeate spring is Turnbridge Wells in Kent, England. Lord Dudley North discovered Turnbridge in 1606 and later wrote: “These waters youth in age renew //Strength to the weak and sickly add //Give the pale cheek a rosy hue //And cheerful spirits to the sad.” [cite].

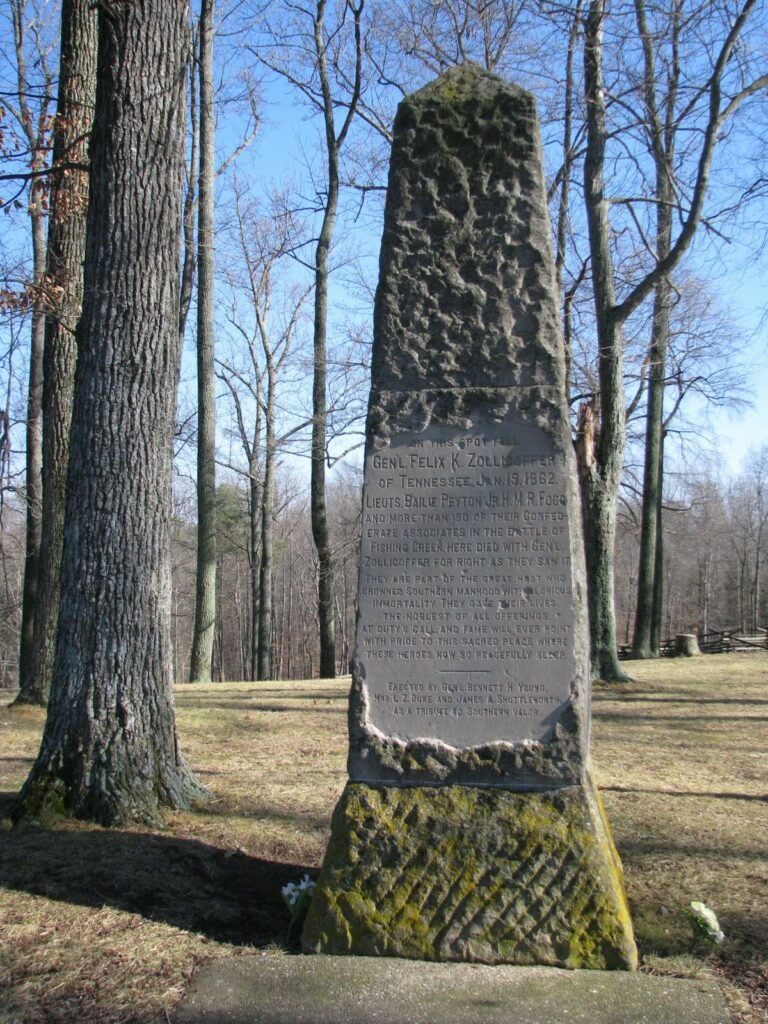

No Destination: Zollicoffer Park Cemetery

Union troops who fell are buried in the Mill Springs National Cemetery, but the Confederate fallen were hastily buried in shallow graves. Locals reburied these dead in a mass grave, but first removing and returning to Tennessee the remains of General Felix K. Zollicoffer.

Union troops who fell are buried in the Mill Springs National Cemetery, but the Confederate fallen were hastily buried in shallow graves. Locals reburied these dead in a mass grave, but first removing and returning to Tennessee the remains of General Felix K. Zollicoffer.

During the Battle of Mill Springs, Zollicoffer accidentally rode on horseback into the Union line (it was raining and smoky from battle) believing it was own. He was killed on the spot and a white oak (the Zollie Tree) was soon thereafter planted to mark the site.

In 1902, ten-year old Dorothea Burton believed it unfair that annual memorials occurred only at the National Cemetery. She believed that the Confederate fallen should be acknowledged, and she took the initiative (with her father’s help) to clear the area around the Zollie Tree and to place a wreath at the site. It soon became an annual tradition, drawing the attention of the United Confederate Veterans Association. By 1910, an obelisk (pictured above, upon which a close examination will reveal bullet marks showing that the obelisk was once used by locals for target practice) was erected to mark the site where Zolliffer died. At the same time, a monument was also erected to mark the mass grave (pictured right). Today, representative markers for the fallen stand nearby though all of the remains continue to lie in the original mass grave site.

In 1902, ten-year old Dorothea Burton believed it unfair that annual memorials occurred only at the National Cemetery. She believed that the Confederate fallen should be acknowledged, and she took the initiative (with her father’s help) to clear the area around the Zollie Tree and to place a wreath at the site. It soon became an annual tradition, drawing the attention of the United Confederate Veterans Association. By 1910, an obelisk (pictured above, upon which a close examination will reveal bullet marks showing that the obelisk was once used by locals for target practice) was erected to mark the site where Zolliffer died. At the same time, a monument was also erected to mark the mass grave (pictured right). Today, representative markers for the fallen stand nearby though all of the remains continue to lie in the original mass grave site.

The area, later designated the Zollicoffer Park Cemetery eventually fell under the control of the Kentucky Department of Parks until 1992 when the Mill Springs Battlefield Association was formed to protect this and other sites associated with the 1862 battle.

No Destination: Mill Springs National Cemetery

Kentucky has seven national cemeteries and has the highest concentration of national cemeteries of any state in the Union. Mill Springs National Cemetery is the smallest cemetery in the national system, though its has existed since the system was first established in late 1862 with only twelve cemeteries. Because of complications associated with the war, it was impractical to create a proper resting place for our nation’s heroes until after the war. Congress in 1867 provided more specifics for the national cemetery system and Mill Springs National Cemetery was formally dedicated on June 15, 1881. Mill Springs Nat’l Cemetery sits atop a high, sloping hill next to the Mill Springs Battlefield Visitor Center (opened in 2006) in the Pulaski County community of Nancy.

Kentucky has seven national cemeteries and has the highest concentration of national cemeteries of any state in the Union. Mill Springs National Cemetery is the smallest cemetery in the national system, though its has existed since the system was first established in late 1862 with only twelve cemeteries. Because of complications associated with the war, it was impractical to create a proper resting place for our nation’s heroes until after the war. Congress in 1867 provided more specifics for the national cemetery system and Mill Springs National Cemetery was formally dedicated on June 15, 1881. Mill Springs Nat’l Cemetery sits atop a high, sloping hill next to the Mill Springs Battlefield Visitor Center (opened in 2006) in the Pulaski County community of Nancy.

The Battle of Mill Springs occurred in January of 1862. During the course of the battle, 39 Union soldiers fell while Confederate losses numbered 125. (Visit the Kaintuckeean on Wednesday for a post about Zollicoffer Park and the Confederate mass grave/cemetery). Prior to the battle, CSA troops had established themselves in the immediate area, though the Union had control of neighboring communities. Confederate attempts to keep the two groups of Union troops from joining were defeated during this battle, and the surviving Confederates fled their position and supplies.

The Battle of Mill Springs occurred in January of 1862. During the course of the battle, 39 Union soldiers fell while Confederate losses numbered 125. (Visit the Kaintuckeean on Wednesday for a post about Zollicoffer Park and the Confederate mass grave/cemetery). Prior to the battle, CSA troops had established themselves in the immediate area, though the Union had control of neighboring communities. Confederate attempts to keep the two groups of Union troops from joining were defeated during this battle, and the surviving Confederates fled their position and supplies.

The Battle of Mill Springs occurred nine days after the Battle of Middle Creek; these two Confederate losses shifted the field of battle from southeeastern Kentucky into Tennessee until the Battle of Perryville brought the war back to Kentucky.

NoDestination: Somerset’s Fountain Square & John Sherman Cooper

Fountain Square, the center of Somerset, was restored in 1963 by Senator John Sherman Cooper and his wife, Lorraine. At that time, Cooper was serving his third stint (1946-49, 1952-55 and 1956-73) as a United States Senator from Kentucky. The Senator was a liberal Republican who also served in the Army, in diplomatic posts to the U.N., East Germany and India as well as a member of the Warren Commission.

Fountain Square, the center of Somerset, was restored in 1963 by Senator John Sherman Cooper and his wife, Lorraine. At that time, Cooper was serving his third stint (1946-49, 1952-55 and 1956-73) as a United States Senator from Kentucky. The Senator was a liberal Republican who also served in the Army, in diplomatic posts to the U.N., East Germany and India as well as a member of the Warren Commission.

Cooper voted for the Civil Rights Act, was one of the first senators to stand up to McCarthyism and was instrumental in barring U.S. military operations in Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

Born in Somerset in 1901, Cooper died in 1991 in Washington. He never forgot his Kentucky roots; from his obituary in the NY Times:

Mr. Cooper worked quietly, avoiding histrionics. He left behind no ringing calls to action, perhaps because he was, by his own admission, “a truly terrible public speaker.” On the rare occasions when he did take the Senate floor, he was often inaudible. He mumbled and swallowed his words, and apparently made no effort to avoid use of Kentucky dialect in which “great” sounded like “grett,” “government” became “guv-ment,” and “revenue” was pronounced “rev-noo.”

He was, however, a man of principle. A man who was elected to serve his constituents and not party leaders. He frequently bucked party leadership to vote his conscience.

Fountain Square is the focal point of Somerset; its center where the Martin Luther King march began and where Somernites car show gathers each summer month. The land is owned by Pulaski County, a determination made following a court order prohibiting the city of Somerset from building a road through the square [cite]. According to the local Commonwealth-Journal, Fountain Square will soon undergo a $1 million renovation complete with improved pedestrian access and a “grand fountain” [cite and cite]. Along with the new Pulaski County Courthouse, it will bring even more activity to this city center.