|

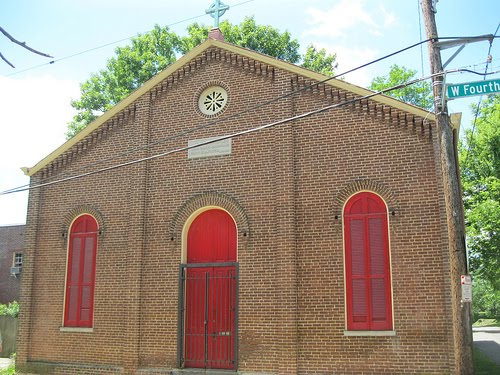

| St. Andrews Episcopal Mission Church – Lexington, Ky. |

A carriage factory on West Fourth Street served as a house of worship for Lexington’s black population from the time Br. Thomas Phillips and his former master, John Brand, opened the Antioch Christian Church in April 1851. Brother Phillips departed this world in 1859, but his congregation continued to grow. In 1874, the old carriage factory was torn down and the congregation built a structure of its own.

One of the most impressive church buildings built for Lexington’s black community immediately following the Civil War, the structure was a simple brick three-bay church with a simple rose window above the inscription, “… the disciples were called Christians first in Antioch.” (Acts 11:26, KJV)

In only a few short years, though, the Antioch (Colored) Christian Church found it necessary to find larger quarters and they relocated to a newly constructed church on Second Street. Thereafter, that church would move again (to Constitution Avenue) but would remain known as the (East) Second Street Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).

The old Fourth Street house of worship would not remain empty for long. Thomas Underwood Dudley, the second Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Kentucky, sought to expand the reach of his Episcopal Church. Overcoming many racist, segregationist views as well as the ghost of his own past as a Confederate veteran, Bishop Dudley pursued an integrated church: “God hath made of one blood all nations of men.”

The Episcopal diocese constructed a new church in the 1950s, but the mission founded by Dudley remained active until that point. Today, the old church structure is inactive and is used by its present owners for storage.

Sources: East Second Street History; NRHP