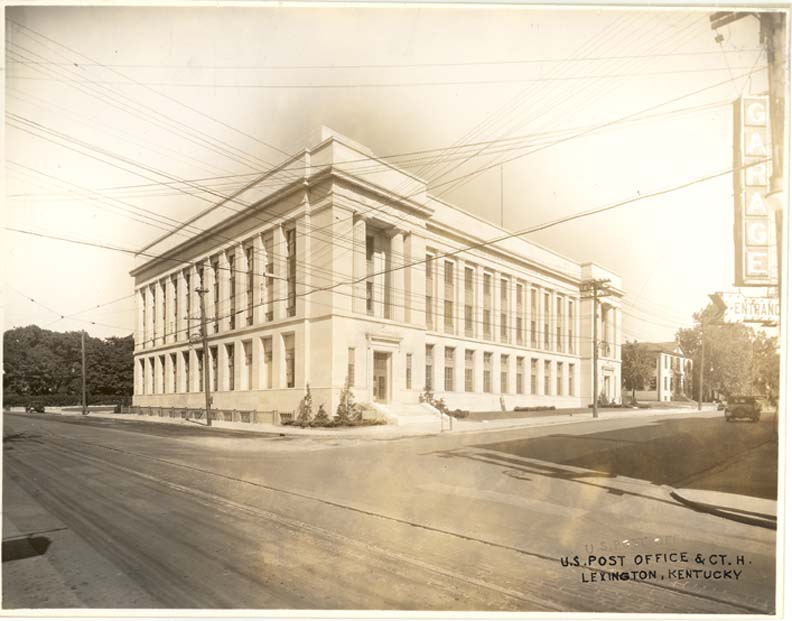

Since it opened in 1934, the Barr Street façade of Lexington’s Federal Building remains unchanged. Its four stories of steel, brick, and limestone construction are a classic example of federal construction in the 1930s (Neo-Classical), evincing the strength of a government and nation fighting off the consequences of the Great Depression. But even this powerful building shows signs of the era’s economics: the central eastern façade (less visible) has a less-costly brick exterior surface. In 1957, an annex was added to the federal building to better accommodate post office operations.

|

| Lexington’s Federal Building, ca. 2013 |

|

| Grand Lobby of the Federal Building – Lexington, Ky. |

Flanking the building’s Barr Street frontage are two projecting pavilions which operate as the building’s primary entrances. Each admits visitors into small anterooms off the central, grand lobby. Originally, the grand lobby operated as the main post office with sorting facilities in adjacent rooms and in the basement. Today, the post office is long gone though vestiges remain in the extensively decorated room comleted with “bronze grills, marble pilasters, and a terrazzo floor.”

The eastern anteroom/lobby features “an elliptical staircase with original wrought iron balusters and a wood handrail” while the lobby has “walls of St. Genevieve Golden Vein marble.”

|

| Courtroom A in the Federal Building, as viewed from the Bench |

On the second floor is the main Courtroom A which remains as it would have appeared when the building opened in 1934, though with the addition of advanced technology necessary for today’s legal system. As described in the National Register application, it is “the most significant space of the upper floors.” The room features a “marble wainscoting, and original acoustical tile walls,” as well as original “Gothic design hanging chandeliers [having] fleur-de-lis and quatrefoil designs” hang from the coffered wood beamed ceiling.”

|

Ward Lockward’s

Daniel Boone’s Arrival in Kentucky |

At the rear of the courtroom, opposite the judge’s bench, is a 1938 mural by Ward Lockwood entitled Daniel Boone’s Arrival in Kentucky. Commissioned by the Section of Fine Arts of the Works Progress Administration, it recalls Boone’s first crossing into Kentucky on a hunting and trapping expedition in the 1760s. Boone would, of course, return to this “promised land” calling “heaven … a Kentucky of a place.” (As legend would have it…)

Behind the bench is a portrait of Judge Cochran who was the first judge to preside in the Eastern District of Kentucky. Appointed in 1901 after the old District of Kentucky was split, Cochran would serve until his death in 1934. Flanking the walls of the courtroom are additional portraits of former and senior status judges from the District.

|

| Grandeur of Courtroom A, as seen from the Jury Box |

Building A Landmark.

During the roaring twenties, Washington and Lexington leaders debated the ideal spot for a new federal courthouse in the city. City leaders opposed the federal governments proposal to erect the courthouse on Short Street at the head of Esplanade, and being owners of the property were quite persuasive.

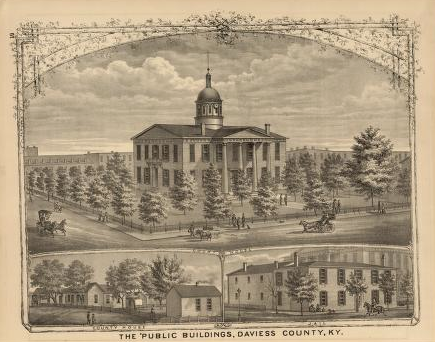

Instead, the northeast corner of Barr and Limestone was selected in the spring of 1930 for the erection of a new federal courthouse and post office, as well as offices for other federal agencies. As a sign of the times, this included offices for the prohibition enforcement agency. The building would be located on a plot running “from Limestone east on Barr to St. Peter’s school, and north on Limestone from Barr to Pleasant Stone Street, or what is known as Sayre College alley.”

A title abstracter, J.W. Jones, was employed by the government and found “no serious defects in the titles to any property which affronts approximately 263 feet on north Limestone street and 213 feet on Barr street.” Though clearing title seemed effortless, property acquisition would not be.

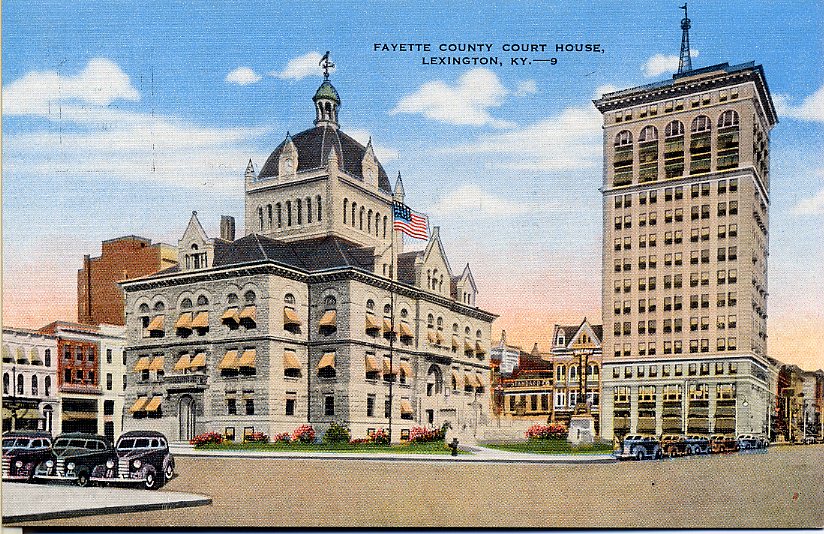

In December 1930, Sawyer Smith – the U.S. District Attorney – instituted condemnation proceedings against those property owners who didn’t voluntarily sell their land. The total land value was appraised at $184,648.50; final judgment in the condemnation suit was entered in early March, 1931. On April 2, 1931, a blanket deed was filed in the Fayette County Clerk’s Office identifying the U.S.A. as owner of the land.

During the heat of late summer and early autumn, 1931, “an adequate force of workmen and equipment” from the Thurman Wrecking & Supply Co. worked to dismantle the old structures on the site of the proposed federal courthouse. But the proposal was not yet complete.

|

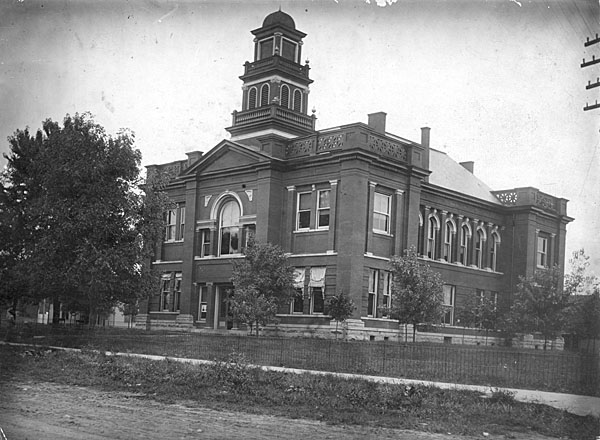

| Old Federal Building at Main and Walnut |

On November 6, 1931, the architect’s drawing of the “New Lexington Postoffice” was published on page one of the Lexington Leader. It was the “first official announcement of plans and specifications today.” Facing Barr street, the 170′ x 125′ structure would be “of classic architecture, according to the Greek motif.” Over the next year, the Churchill and Gillig architectural firm worked to finalize plans for the new federal building. As is often the case, it came down to the last minute. The Lexington Leader writes on March 1, 1932, “Nine draftsmen worked all night Monday … and completed plans for Lexington’s $761,000 federal building.” Plans were then taken for a “final check by Brinton B. Davis [of Louisville], consulting architect on the project, prior to final review and approval by Louis A. Simon, Superintendent of the Architectural Division of the Treasury Department.

With deeds acquired, land cleared, and plans approved, construction could commence!

In December 1934, the post office and other federal offices were finally moved from the old federal building at Main and Walnut) to the new building at Limestone and Barr streets.

Postal Operations and First Class Mail.

When the Post Office opened on Barr Street, the cost to send a first class letter was 3¢. The price was unchanged when many of the post office operations were relocated in 1957 to an annex on the building’s north side. As Lexington continued to grow, the Federal Building became inadequate to serve as Lexington’s main mail sorting facility.

In 1973, the Lexington post office office was relocated to Nandino Blvd and Georgetown Road and the old post office in the Federal Building became the Barr Street Station. At the time, the cost to mail a first class letter had risen to 8¢.

Security and convenience (i.e., parking) gave way to yet another change for downtown’s postal needs in April 1998 (first class letter, 32¢) when the Barr Street Station itself was closed. Downtown PO boxes were relocated to a new, modern post office on East High Street. The modern post office, however, carries a historic name: Post Rider Station hearkening to our nation’s earliest history when mail was carried over post roads by post riders on horseback and delivered to a central location in each town or community.

|

Above the entry to the U.S. Marshals Office for the

Eastern District of Kentucky |

Though no postal service activities remain in the Federal Building, it remains an active federal building housing the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky as well as the Office of the United States Marshals for the Eastern District of Kentucky. Among other tasks, the Marshal’s Service provides security for the federal Courts. Of course, the Marshall’s of Eastern Kentucky have been made famous by the popular FX television program Justified. Fans of the show know that Raylan Givens, a Harlan County native portrayed by Timothy Olyphant, is a U.S. Marshal. A real U.S. Marshal will advise that Givens’ office space is quite spacious and a far cry from the quarters offered the U.S. Marshals at the end of the Federal Building’s grand lobby.

Additional photos of the Federal Building may be found on flickr.

The Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation hosts a monthly deTour for young professionals (and the young-at-heart). The group meets on the first Wednesday of each month at 5:30 p.m. Learn more details about this exciting group on Facebook! You can also see Kaintuckeean write-ups on previous deTours by clicking here.

Sources: Andrew Dart; KDL (Asa Chinn); local.lexpublib.org; National Archives