|

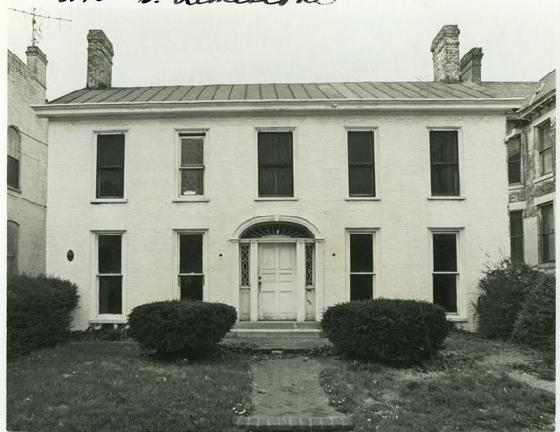

| The Oldham House – Lexington, Ky. |

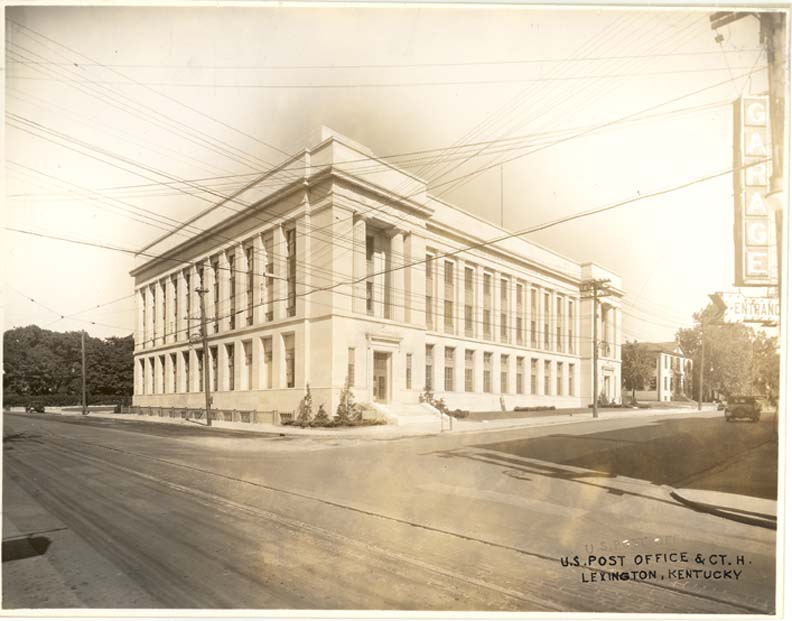

The names Samuel and Daphney Oldham don’t ring out among the most famous in Lexington’s storied history. Like many in Lexington’s early years, their stories began in Virginia. But they, and their ca. 1835 home at 245 South Limestone Street (then 95 South Limestone, or South Mulberry), represent a unique part of our community’s African-American heritage.

|

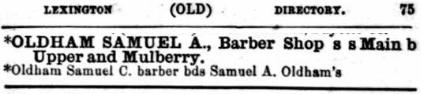

| Listing from Lexington City Directory, ca. 1864 |

Samuel A. Oldham was an enterprising barber and business owner when he and his wife built their home on what was then Lexington’s southern edge. But at the start of the 1826, Oldham was enslaved. During the course of the year, he would purchase his own freedom. In 1830, he transacted for the freedom of his wife and sons. The freed black family thereafter built the two-story, five-bay common bond brick house.

In 1839, the Oldhams sold the home to William R. Bradford. Though they lived there only a short time, their ownership was marked as the first time a freed slave at owned a home in Lexington. In 2008, their South Limestone home was the inspiration for a one-woman act portraying Daphney Oldham. In In This Place, Daphney told her story of being born into slavery but dying as a free woman of color. The show was a collaborative effort between LexArts and director Ain Gordon; thanks be to God, Ain has published the entire performance on Vimeo:

Ain Gordon’s IN THIS PLACE… from Ain Gordon on Vimeo.

|

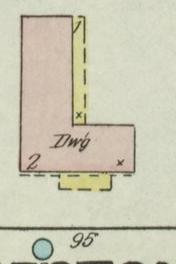

| 1890 Sanborn Map of then 95 S. Limestone/Mulberry |

Like the Oldham’s, Bradford owned 245 S. Limestone for only a few years. It was purchased in 1845 by Juretta Shepherd,a widow, who five years later would marry Dr. Joseph G. Chinn. Attorneys kept the couple’s finances separate and it appears that Dr. Chinn, who would serve as a councilman and mayor of Lexington, never had an ownership interest in the property. Mrs. Chinn died in 1872 and the property was sold as the result of a lawsuit brought in 1877.

The property would transfer hands many times over the following century-plus. Over the years, it would be utilized as “a single family home, an antique store, apartments, and eventually a rooming house.”

The house became quite dilapidated.

|

| Oldham House, ca. 1965 Photo: BGT/KDL |

As you can see from the ca. 1965 photo above, the old house was beginning to show signs of her age and lack of maintenance. It was listed on the Blue Grass Trust’s most endangered properties list in 2000. In 2004, the owner sought a permit to raze both the Oldham House and an adjoining structure; the Board of Architectural Review denied the request. The building was one of the most blighted structures on South Limestone; in fact, Hayward Wilkirson was quoted in a 2006 Herald-Leader article as describing South Limestone as a “gap-tooth grin” in the Historic South Hill Neighborhood. Of course, Wilkirson was referring to the Oldham House in the article entitled “Historic home needs loving owner.”

|

| Oldham House, ca. 2007 Photo: Gilpin Masonry |

A new owner was found: local builder Coleman Callaway III bought the property in early 2006 for $175,000. At that time, squatters had been the building’s most recent occupants; they had started fires to keep warm. There were holes in the roof and hardwood floors were no longer connected to floor joists or the foundation. As you can see from the photo at right, the condition of the property was nothing less than poor.

In December 2006, the home’s savior entered into a fight with the architecture review board (BOAR) over a sloped-roof addition Coleman had added to the rear of the structure. BOAR found the addition was 4 1/2 feet too wide and the sloped-roof was not in keeping with the architectural style. Seven months later, the planning commission overruled the BOAR.

An op-ed in the Feb. 4, 2007, Herald-Leader summed up the situation quite well in: “Lexington’s desire and ability to connect with the past is fantastic and, in many ways unique among growing, forward thinking cities. But our love for history and tradition should not blind us from the reality of the modern day.”

Additional photos of the deTour of the Oldham House can be viewed on flickr.

Sources: ancestry.com; BGT; LBAR; local.lexpublib.org; Merlene Davis (H-L); Rootsweb

The Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation hosts a monthly deTour for young professionals (and the young-at-heart). The group meets on the first Wednesday of each month at 5:30 p.m. Learn more details about this exciting group on Facebook! You can also see Kaintuckeean write-ups on previous deTours by clicking here.