The Bluegrass Trust for Historic Preservation hosts a monthly deTour to a local historic site that has been well-preserved and restored – the group meets on the first Wednesday of each month at 5:30 p.m. Details are always available on the Kaintuckeean Calendar and on Facebook! In September 2011, the deTour group visited three carriage houses; this is the first installment. More pictures from this deTour are available on flickr.

|

| Carriage House behind the Hunt-Morgan House – Lexington, Ky. |

Behind the stately Hopemont on North Mill Street is the home’s carriage house. A carriage house, like the carriage, is a relic of centuries past. Today’s automobile and garage were preceded by horse-drawn carriages and these carriages (and their noble steeds) required protection from the elements. And unlike today’s two-car garages, a carriage house was never attached to the residence it served (even without carbon monoxide issues!).

Hopemont, built in 1814, preceded the above carriage house by some twenty years. It is quite unlikely that John Wesley Hunt – believed to be Kentucky’s first millionaire – would have built Hopemont without an accompanying carriage house. On this notion alone, one must conclude that the pictured carriage house was the home’s second. Although much of the interior structure is original, the carriage house was slightly modified at the turn of the twentieth century, i.e. circa 1900.

It is said that John Wesley Hunt’s nephew, John Hunt Morgan – the famed “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy,” stalled his famous Black Bess in the carriage house. And although the legend has been told in different ways, one version is as follows: General Morgan saddled Black Bess in the carriage house before riding through the rear of the Hunt-Morgan House only to stop and kiss his mother on the cheek before galloping out the front door.

Of course, Black Bess has been immortalized herself in another way when artist Pompeo Coppini sculpted a masculine mare upon which General Morgan would forever bestride in front of the old courthouse in Lexington. Yes, this famous mare is likely the most infamous ‘tenant’ of the Hunt-Morgan House carriage house.

Bibliography

Alvey, R. Gerald. Kentucky Bluegrass County (p.64-65)

Federal Writers Project, Kentucky: A Guide to the Bluegrass State (p. 204)

First, the

First, the

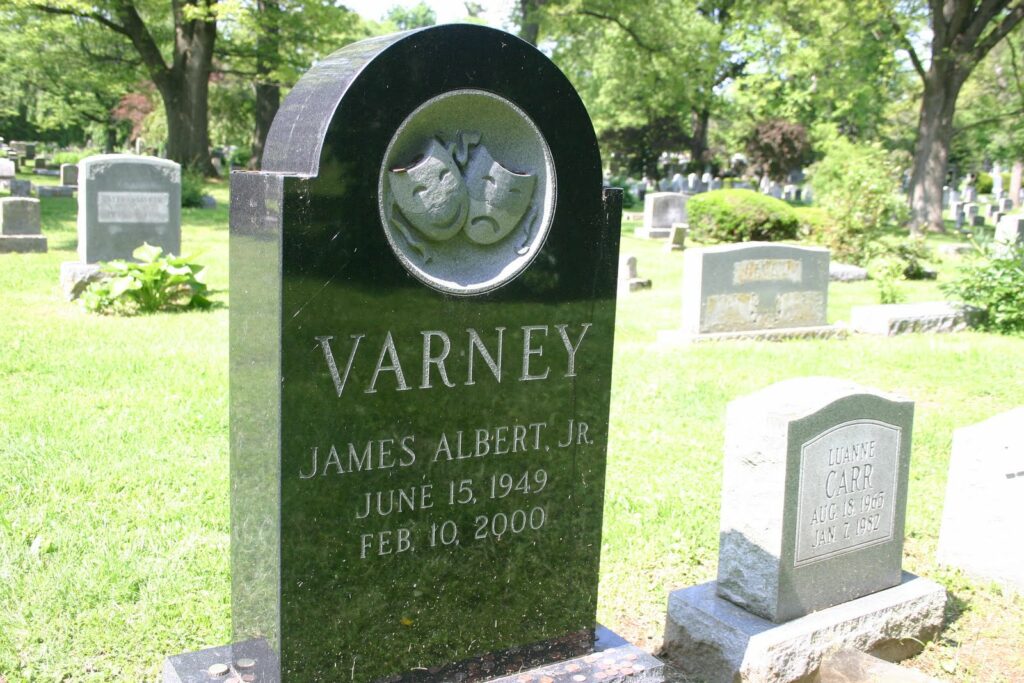

Ernest made his first appearance in an advertisement for Bowling Green’s Beech Bend Park in 1980. Ernest was just one of Varney’s many characters that usually found their way into Ernest movies or TV specials, of which there were more than a dozen. I absolutely LOVED Ernest movies as a kid, and while back I watched a couple of his movies again. I was shocked to discover that they’re still pretty funny as an adult.

Ernest made his first appearance in an advertisement for Bowling Green’s Beech Bend Park in 1980. Ernest was just one of Varney’s many characters that usually found their way into Ernest movies or TV specials, of which there were more than a dozen. I absolutely LOVED Ernest movies as a kid, and while back I watched a couple of his movies again. I was shocked to discover that they’re still pretty funny as an adult.