|

| Cannon on the front lawn at UK. UK Libraries. |

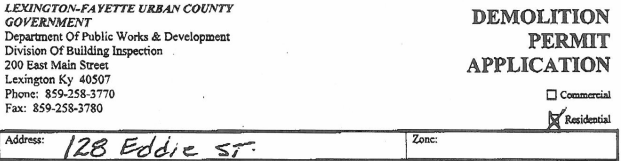

An oft-forgotten conflict in American history, the Spanish-American War was one of only five wars in the nation’s history to be formally declared by Congress. Lasting only three months in 1898, the island of Cuba served as the conflict’s main theatre.

The final battle of the war was staged in the hills to the immediate east of Santiago and it acquired the name The Battle of San Juan Hill. A month after the battle, a dispatch was sent from the Secretary of War to General Shafter in Cuba requesting that “a lot of old brass cannon, old style, at Santiago, captured by you.”

These many cannons were ultimately distributed by the War Department throughout the country. One in particular has since 1903 been on the grounds of the University of Kentucky, though it didn’t arrive directly but was instead “regifted” through multiple hands before arriving in front of the University’s Main Building.

|

| Author’s collection. |

The stock of the UK cannon bears the markings of Barcelona, Spain and a date from October 1795. Over a century later, the war was fought and the old style cannons were captured by the U.S. War Department. According to UK, the cannon was presented to the Commonwealth of Kentucky which in turn gave the cannon over to Lexington Mayor Henry T. Duncan. It is unclear how the Commonwealth fits into the picture, as the majority of other accounts reflect that the cannon was on loan from the War Department to the City of Lexington “as a souvenir.”

The engraving on the limestone block that supports the cannon, nearly illegible now from the years, reads:

Spanish trophy Federalista, received from the United States War Department by City of Lexington, June 18th, 1900. Transferred to State College of Kentucky. May 19th, 1903, through Mayor Henry T. Duncan.

Immediately after its receipt by Lexington, the cannon was displayed at an Elks Fair. After the fair, the Federalista (as it would be nicknamed because of an engraving on the barrel of the cannon) was promptly deposited under an American flag in a warehouse on Upper Street and both forgotten and nearly lost for a years time. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, the people of Lexington (and Mayor Duncan) had no conviction about where to place the war relic. A proposal to place the cannon at Cheapside near the old courthouse drew at least one letter to the editor of the Lexington Leader:

I think it will be a great mistake to place the Spanish cannon on Cheapside, as has been suggested in the paper. All of the city of Lexington is not concentrated on Cheapside, and the few statues or ornaments should not all be huddled together and crowded into one little space. One detracts from the other, and such statues or mementos as Lexington may be preserved.

By May of 1903, Mayor Duncan determined that the State College (later known as UK) would be a fitting site for the cannon. Installed on May 19, 1903, the Lexington Leader had this to say about the installation ceremony:

One of the prettiest ceremonies ever performed at State College was the unveiling of the cannon this afternoon, presented by the city of Lexington. The large crowd present showed the high esteem in which State College is held by the people of Lexington, and the cadet battalion in their gray blouses and white duck trousers made a natty appearance on parade.

|

| The Federalista after a prank. UK Libraries. |

On campus, the Federalista became a backdrop for “picture-taking and campus hazing activities.” Campus lore suggests that it was fired after wins by the Wildcats and photographic evidence shows it being toppled. Reports of it being pivoted toward the Main Building and filled with manure before being fired exist as to suggestions that Main Building windows were at many times broken from the blasts of the cannon. As a result of either the truth or threat of these things, or a combination thereof, the cannon was cemented in several decades ago.

The August 28, 1942 issue of the

Kentucky Kernel indicates that the student-run newspaper spearheaded a campaign to have the relic from the Spanish-American war scrapped as part of the WWII war effort. The effort was not unique. Across the country, national fervor during World War II prompted the smelting of many historic relics with the proceeds being used for war bonds and the metal finding its way into the war effort as well. This, too, was the case with a cannon in

Bloomington, Illinois which shares the history and profile of the cannon at the University of Kentucky. Both barrels were made at Barcelona and appear identical. The Bloomington cannon barrel weighed “5,695 pounds of which 80 percent was copper, 10 percent tin, 8 percent lead and the remaining amount silver.” One can presume that the UK cannon has the same statistics.

Fortunately, the cannon remains on campus. Its green hue – that of tarnished brass – has endured as well. In 1934, the

Kentucky Kernel suggested that the University might be benefited by making the cannon “sensational. … Steps should be taken by the proper authorities on the campus to have the green coat removed and the shining natural color of the brass take its stead.”

“That piece of rare war machinery faces a muchly traveled highway and were it gleaming in the sunlight it would catch the eye of more than one tourist who would stop a few minutes to inspect it and then visit the remainder of the campus. The advertising value of this would well repay for the shining of the weapon of former days.”