|

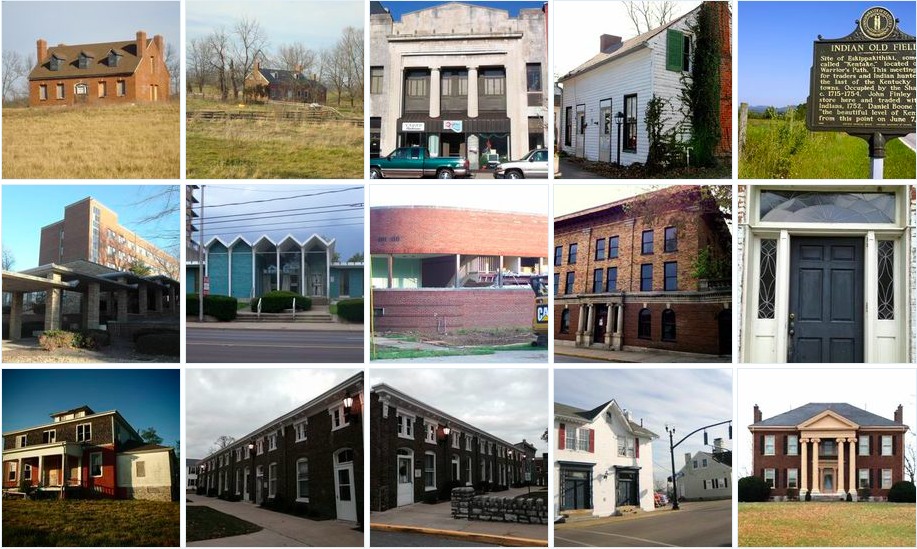

| Photographs of Select Sites on the Blue Grass Trust’s Eleven in Their Eleventh Hour List |

Each year, the Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation assembles a list of historic central Kentucky properties which are threatened. For the 2015 edition of the “Eleven in Their Eleventh Hour” list, the BGT has looked primarily beyond Fayette County to sites across 11 central Kentucky counties.

The list of counties largely resembles those included in the 2006 World Monument Fund’s designation of the Inner Bluegrass Region. The Blue Grass Trust included Madison County on its “11 Endangered List” while omitting Anderson County. All Kentucky counties, however, have “at risk” structures and deserve the attention of preservationists.

The BGT’s list is a great step toward recognizing that preservation can and should occur throughout Kentucky and not only in our urban cores. The 14 structures within the 11 counties also reflect that theme.

According to the BGT, “the list highlights endangered properties and how their situations speak to larger preservation issues in the Bluegrass. The goal of the list is to create a progressive dialogue that moves toward positive long-term solutions. The criteria used for selecting the properties include historic significance, lack of protection from demolition, condition of structure, or architectural significance.”

The sites are listed below.

Bourbon County – Cedar Grove & John T. Redmon House

Both Cedar Grove and the Redmon House are architecturally significant houses from the early 19th century. The circa 1818 John & John T. Redmon House has a steep roof more often found in Virginia than Kentucky and has lost its original one-story wings. Though both buildings are vacant, they have undergone partial renovations recently and the BGT believes these structures could be still restored.

Boyle County – Citizens National Bank & Dr. Polk House

Mostly empty for two-plus years, the Citizens National Bank building at 305 West Main Street in Danville was built in 1865 with a double storefront that housed First National Bank of Danville and a drug store. Bank-owned and listed for sale, a demolition (or partial demolition) of this structure could affect adjacent structures with which the building shares walls. Dr. Polk House at 331 South Buell Street in Perryville sits across from Merchants’ Row and is arguably the historic landmark most in need of restoration in the downtown. Built in 1830 as a simple Greek Revival house with two chimneys and two front doors, the structure was purchased by Dr. Polk in 1850. A graduate of Transylvania University, he was the primary caretaker of wounded from the Battle of Perryville and his 1867 autobiography details the gruesome battlefield.

|

| Dr. Polk House in Perryville, Kentucky. Photo courtesy of the BGT. |

Clark County – Indian Old Fields

Indian Old Fields in Clark County was the location of Eskippakithiki, the last known Native American town in what became Kentucky. Located on Lewis Evans’ 1755 map of Middle British Colonies, this highly important site was significantly impacted during construction of a new interchange (which opened September 2014) for the Mountain Parkway crossing KY 974 near the center of the Indian Old Fields.

The Kentucky Heritage Council noted in 2010 that “’Indian Old Fields,’ is a historic and prehistoric archaeological district of profound importance,” with 50 significant prehistoric archaeological sites identified within 2 kilometers of the interchange. These sites cover the Archaic Period (8000-1000 BC), Woodland Period (1000 B.C. -1000 AD) and Adena Period (1000-1750 AD), with several listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These include villages, Indian fort earthworks, mounds, sacred circles and stone graves. The site also has substantial ties to the famous Shawnee Chief Cathecassa or Black Hoof, Daniel Boone, and trader John Finley.

With the new $8.5 million dollar interchange now open, there are significant concerns that these sites with be under threat from pressure to further develop the area.

Fayette County – Modern Structures

The Blue Grass Trust’s 2014 “Eleven in Their Eleventh Hour” focused on the historic resources at the University of Kentucky. Many of those included on the list (and most of those demolished) were Modern buildings designed by locally renowned architect Ernst Johnson. Research into Johnson’s work by the BGT and others such as architects Sarah House Tate and Dr. Robert Kelley was joined with education and advocacy programming focused on his architecture and legacy as a master of Modernism. This research and programming led to other efforts by the Blue Grass Trust, namely working to educate the public on the historic value of mid-century architecture.

In our continued education and advocacy effort surrounding these structures, the Blue Grass Trust lists Fayette County’s mid-century Modern architecture as endangered. Often viewed as not old enough or not part of the traditional early fabric of Lexington and surrounding areas, the Modern buildings of the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s are being substantially and unrecognizably altered or demolished. It is important to recognize that buildings 50 years of age are eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a length of time deemed appropriate by the authors of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 for reflection on an era’s importance. Read more from the Kaintuckeean’s earlier post on the People’s Bank branch on South Broadway.

%2BBank%2B(Photo%2Bby%2BRachel%2BAlexander).jpg) |

| People’s Bank in Lexington. Photo by Rachel Alexander. |

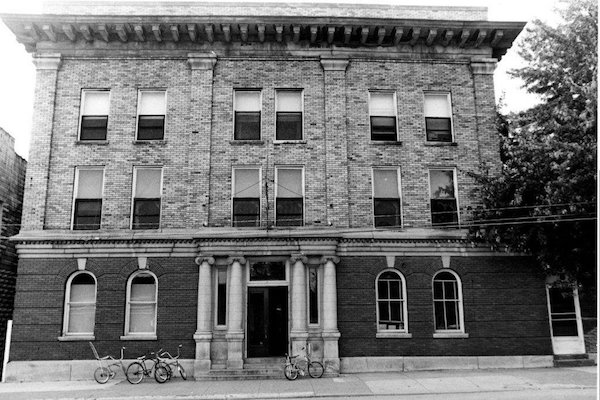

Franklin County – Old YMCA & Blanton-Crutcher Farm

Both the Old YMCA in downtown Frankfort faces potential demolition and the Blanton-Crutcher Farm in Jett are slowly deteriorating from neglect and both structures are worth saving. The 1911 Old YMCA at 104 Bridge Street in Frankfort, designed in the Beaux Arts style by a a Frankfort architect, was a state-of-the-art facility featuring a gymnasium, indoor swimming pool, bowling alley, meeting rooms and guest quarters. While a local developer is hoping to transform it into a boutique hotel, there is also a push by the city of Frankfort to demolish this structure. If saved, this could be a transformative project in our capital city.

The Blanton-Crutcher Farm in Jett includes an architecturally and historically significant circa 1796 house built by Carter Blanton, a prominent member of the Jett farming community. In 1831, Blanton sold the farm to his nephew, Richard Crutcher, the son of Reverend Isaac Crutcher and Blanton’s sister, Nancy Blanton Crutcher. The 1974 National Register nomination for the farm notes: “The Crutchers were excellent farmers. Three generations of the family farmed the land and made improvements on the house until 1919 when the property was sold. It has remained a working farm with a large farmhouse, at its center, that has evolved over 180 years of active occupation.” In the 1880s, Washington Crutcher significantly increased the size of the house, turning it into the Victorian house that stands today (although the porches were removed due to deterioration and other modern features have been added).

Harrison County – The Handy House aka Ridgeway

The Handy House, also known as Ridgeway, is located on US 62 in Cynthiana, KY. The nearly 200-year-old house was built in 1817 by Colonel William Brown, a United States Congressman and War of 1812 veteran. The farm and Federal-style house were also owned by Dr. Joel Frazer, namesake of Camp Frazer, a Union camp during the American Civil War. In the 1880s, the house underwent significant renovations by W. T. Handy, the owner from 1883-1916 and for whom the house remains named.

The Handy House checks almost every box when it comes to saving a structure: an architecturally and historically important house in good enough shape to rehabilitate, a listing on the National Register of Historic Places, qualification for the Kentucky Historic Preservation Tax Credit, and a group, the Harrison County Heritage Council and a descendant of the original owner, willing to take on the project. Unfortunately, the Handy House is jointly owned between the city and the county. County magistrates voted to tear it down, and the city opted not to vote on it with the hopes that the new council will come to a deal with the Harrison County Heritage Council, which has offered to purchase and restore the house as a community center. Read more from the Kaintuckeean’s earlier post on Ridgeway.

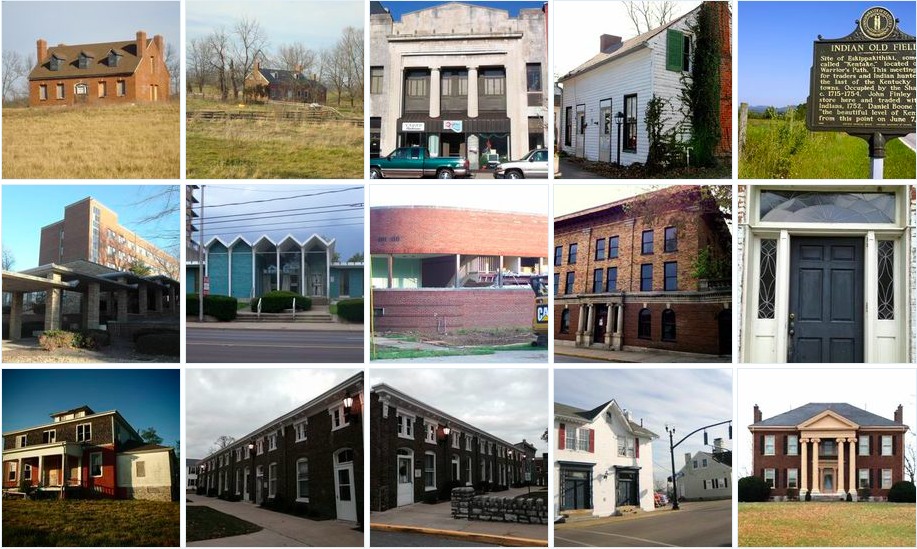

Jessamine County – Court Row

Completed in 1881, Nicholasville’s Court Row is located right next to the Jessamine County Courthouse. Italianate in design and largely unchanged exterior-wise, Court Row is one of the most significant and substantial structures in downtown Nicholasville.

In a broad context, the listing of Court Row is a comment on the status of all the historic resources in downtown Nicholasville. Several threats exist that are culminating in drastic changes to the fabric of the town. Foremost, Nicholasville failed in 2013 to pass its first historic district, an overlay that would have encompassed the majority of the downtown and helped to regulate demolition and development. Then, within the past month, two historic structures were demolished, including the Lady Sterling House, an 1804 log cabin very close to the urban core. Additionally, Nicholasville is on the ‘short list’ for a new judicial center, the location of which has yet to be determined but will almost certainly have an effect on the downtown. Together, these threats present the potential for the loss of significant portions of Nicholasville’s charming downtown.

Madison County – Downtown Richmond

Preservation has had a lot positive movement in Richmond. The Madison County Historical Society is active; the beautiful Irvinton House Museum is city-owned and the location of the Richmond Visitor’s Center; and the downtown contains a local historic district. Like most local historic districts (also known as H-1 overlays), though, the Downtown Richmond Historic District protects historic buildings and sites that are privately owned. That means that city- and county-owned sites are exempt from the H-1 regulations.

The potential damaging effects of this can already be seen. In February 2013, downtown Richmond lost the Miller House and the Old Creamery, two of its most historic buildings. Both were in the Downtown Richmond Historic District and on the National Register of Historic Places. Owned by the county, the buildings were demolished with the hopes of constructing a minimum-security prison on the site that would replicate the exterior façade of the Miller House, according to Madison Judge/Executive Kent Clark. There are several other historic sites in the urban core that are owned by either the city or the county, leading to worry about the state of preservation in Richmond’s downtown.

Mercer County – Walnut Hall

Built circa 1850 by David W. Thompson, Walnut Hall is one of Mercer County’s grand Greek Revival houses. A successful planter and native of Mercer County, Thompson left the house and 287 acres of farmland to his daughter, Sue Helm, upon his death in 1865. In 1978, Walnut Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places along with two other important and similar Mercer County Greek Revival houses: Lynnwood (off KY Highway 33 near the border of Mercer and Boyle Counties) and Glenworth (off Buster Pike).

The James Harrod Trust has notified the Blue Grass Trust that the house may be under threat of demolition, as it is owned by a prominent Central Kentucky developer known to have bulldozed several other important historic buildings.

Scott County – Choctaw Indian Academy

Located in Blue Springs, KY, off Route 227 near Stamping Ground, the Choctaw Indian Academy was created in 1818 on the farm of Colonel Richard M. Johnson, who served as Vice President of the United States under Martin Van Buren (1837–1841). The Academy was created using Federal funding and was intended to provide a traditional European-American education for Native Americans boys. (It was one of only two government schools operated by the Department of War – the other being West Point.) Originally consisting of five structures built prior to 1825, only one building – thought to be a dormitory – remains. By 1826, over 100 boys were attending the school, becoming well enough known to be visited by the Marquis de Lafayette in 1825. The school was relocated to White Sulphur Springs (also a farm owned by Colonel Johnson) in 1831. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Read more about the site from the Kaintuckeean’s earlier post on the Choctaw Indian Academy.

.jpg) |

| Remaining structure of Choctaw Indian Academy. Photo by Amy Palmer. |

Woodford County – Versailles High School

Located on the corner of Maple Street and Lexington Pike in Versailles, the Versailles High School is a substantial structure built in 1928. The building operated as a high school for 35 years before becoming the Woodford County Junior High in 1963, operating as a middle school until being shuttered in 2005. After 77 years of continuous operation, the building has been empty for nearly 10 years.

With no known maintenance or preservation plan, concern exists that the historic Versailles High School will deteriorate from neglect and, ultimately, be demolished.

You can learn more about the Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation on its website, www.bluegrasstrust.org.

%2BBank%2B(Photo%2Bby%2BRachel%2BAlexander).jpg)

.jpg)