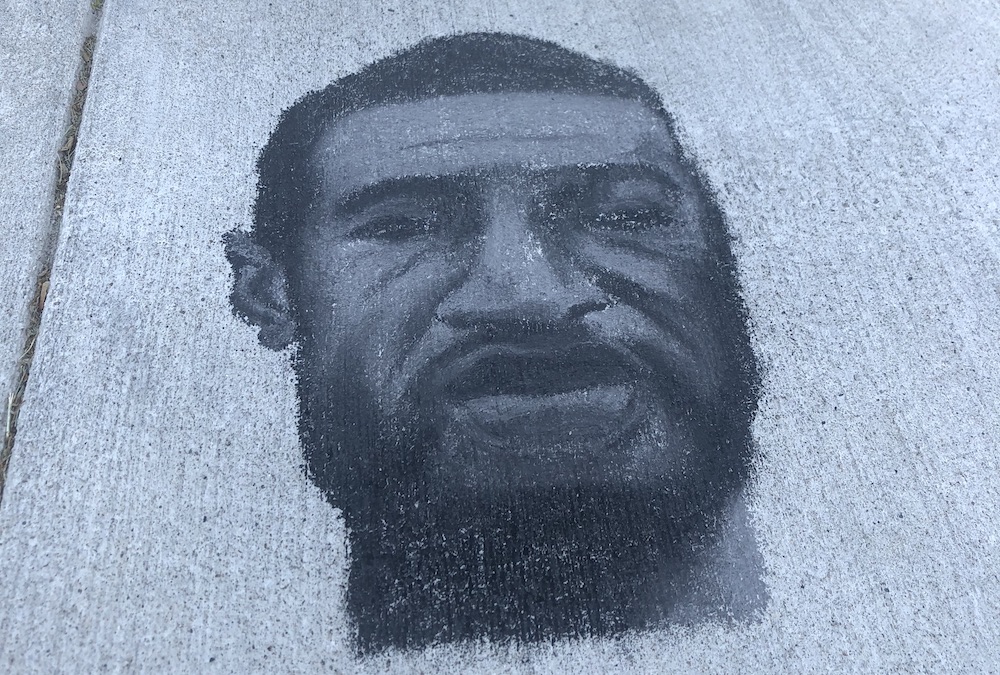

Throughout our nation, protestors are righteously standing up to police overreach and brutality. Protestors gather in remembrance of the many people of color whose lives have been tragically cut short by legal tactics that have been labeled as a form of modern-day lynching. Protestors gather to remember. They gather to say his name: George Floyd. To say her name: Breonna Taylor.

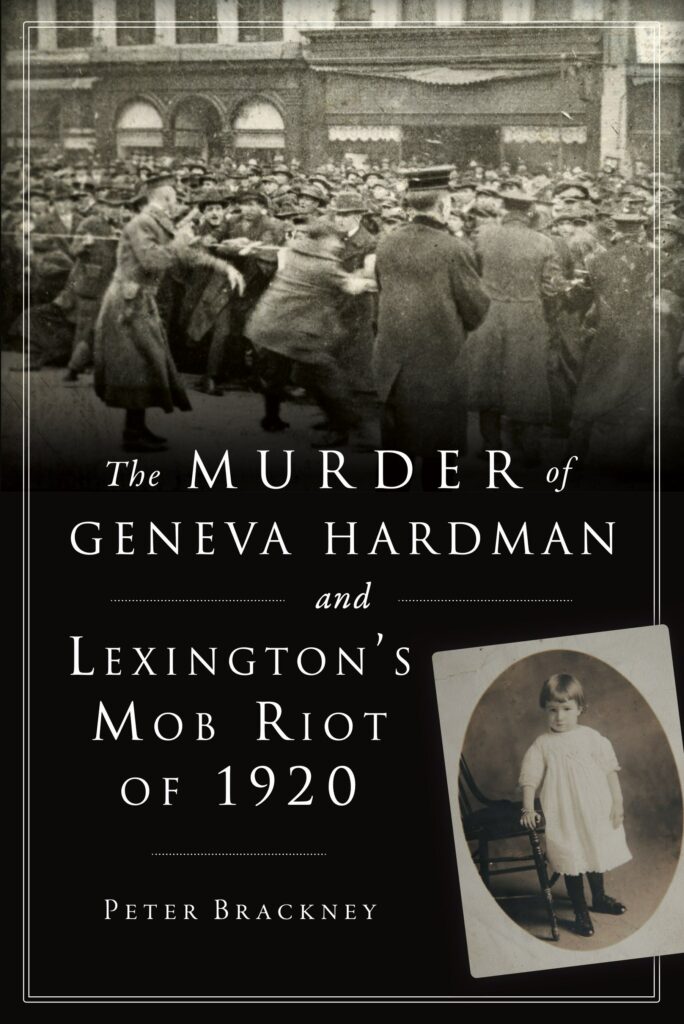

Earlier this year, my book The Murder of Geneva Hardman and Lexington’s Mob Riot of 1920 was published. In it, I included a paraphrase of a quote attributed to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He said, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” I’ve thought a lot about that quote over the past week because, watching the news, I question how far we have come as a nation.

I could not help but compare (and contrast) what is happening today following the murder of George Floyd with what took place a century ago in Lexington, Kentucky following the arrest of Will Lockett. These two men of color were accused of very different crimes and they received very different treatment. This is especially so given that a century had lapsed between these two events. How has that arc of the moral universe evolved?

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Crimes Committed

1920

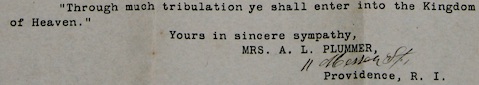

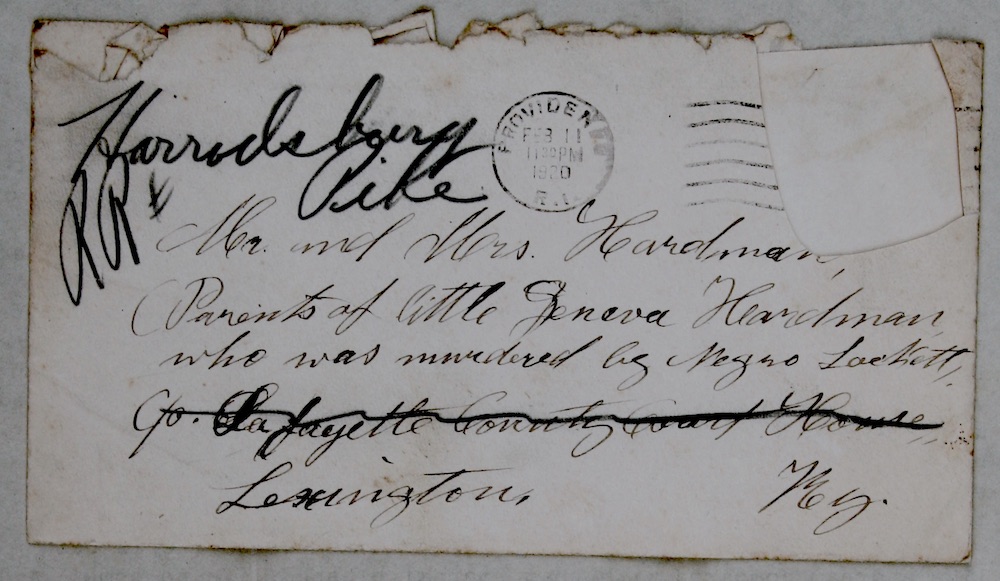

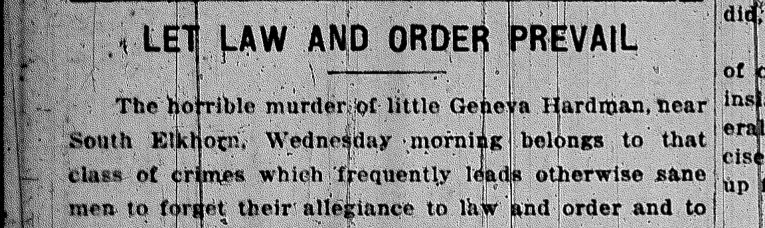

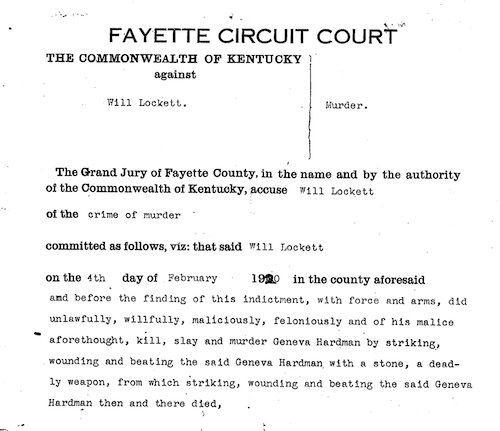

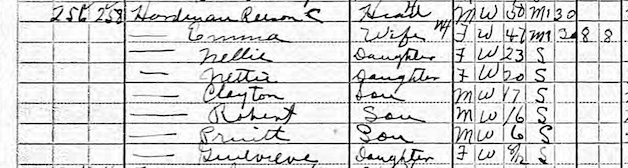

In southern Fayette County, Kentucky, a ten-year old girl – Geneva Hardman – was brutally murdered and quite likely sexually assaulted.

2020

In Minneapolis, Minnesota, an employee at a deli called 911 to report that he believed a counterfeit $20 bill had been used to purchase cigarettes.

The Immediate Response

1920

Without hesitation, the focus was on Will Lockett. Lynch mobs began to form with the purpose of hunting down the accused. Police and sheriffs deputies from three counties also searched for several hours before Will Lockett was apprehended by Dr. Collette and Officer White of the Versailles Police Department. In soiled and bloodstained clothes, Lockett was put into the back of a vehicle and transported downtown to the Lexington Police Department’s headquarters. There, Will Lockett confessed to having committed the crime of which he was accused.

2020

Police responded to the scene. Within 17 minutes after the police arrived, Mr. George Floyd was “unconscious and pinned beneath three police officers, showing no signs of life.”* One officer had kept his knee on Mr. Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds — far longer than George Floyd maintained consciousness.

Protestors Gather

1920

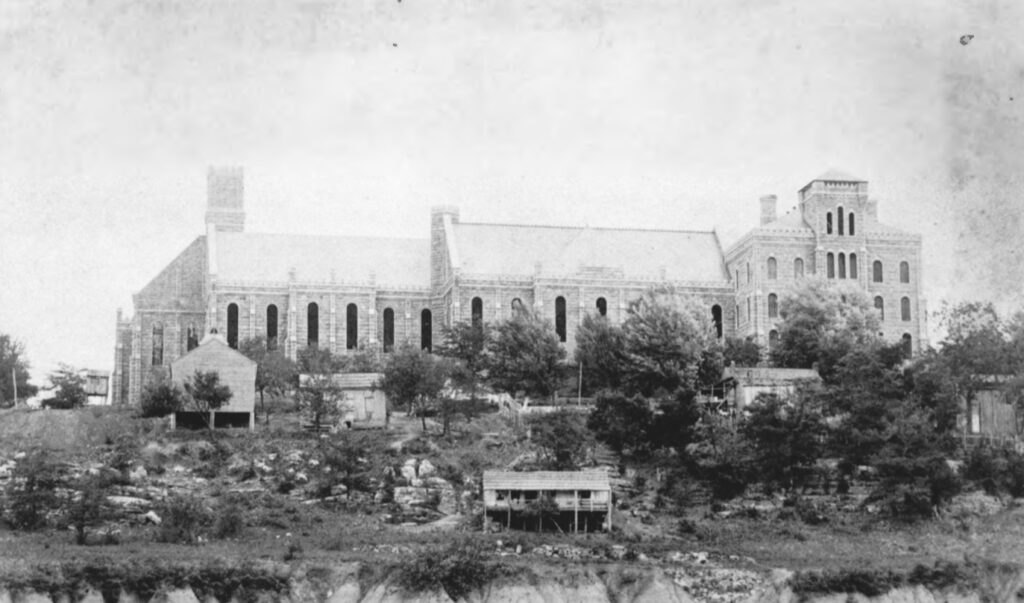

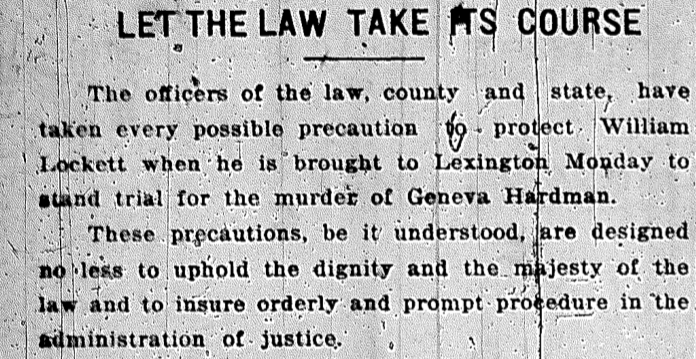

In 1920, the lynch mob did not stop their desire for vengeance. They searched the police station and then the jail, but local and state officials did what they could to protect the confessed murderer. (Was the confession coerced? A valid question and one explored in the book. The justice system of 1920 functioned quite differently than the justice system should function in 2020.) Five days on, Lockett’s trial was held in the Fayette County Courthouse. Outside the courthouse, thousands gathered. Some in the group surged forward, and soldiers stationed around the courthouse responded.

2020

The night following George Floyd’s murder, many gathered in Minnesota’s Twin Cities to protest specifically against the police tactics utilized in Floyd’s death and more broadly against the systemic racial inequality that has plagued this country for more than 400 years. These protests have spread across the United States into all fifty states as well as overseas. Although some protests have become violent, they have remained largely peaceful.

Shots Fired & National Awareness

1920

As the mob in front of the courthouse in Lexington began to surge, Lockett’s defense counsel was delivering closing remarks pleading that his client might be saved from execution. Shots rang out in a volley that resulted in the deaths of six protestors.

The murder of Geneva Hardman, the Lockett trial, and the declaration of martial law was picked up by newswires and carried nationally including multiple stories in the New York Times.

2020

Just as shots were fired a century ago in Kentucky, shots rang out at the crowd in the city of Louisville. Though protests in Louisville have been largely peaceful, there have been some incidents of property damage (including the loss of Louis XVI hand) and violence. On June 1, however, David McAtee was shot and killed by police while operating his bbq stand after midnight. It is unclear what precisely took place because police had deactivated their body cameras. Kentucky is once again the focus of national attention for its state of emergency.em

Looks like Martial Law

1920

Following the shooting outside the courthouse, martial law was declared in Lexington, Kentucky for about two weeks to ensure no more violence occurred. Although the initial show of force was strong with bayonets fixed marching down Main Street, local officials were permitted to function and life was largely normal. It was a sort of “martial law light.”

2020

Images of police in riot gear across the nation. Clearing areas of peaceful protest even before an imposed curfew. Guardsmen on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Although martial law has not been declared, there is a sense that in part of America that there is at least the appearance of martial law.

Perspective

There are parts of these stories which are easy to contrast: a crime committed by a person of color and an escalated response.

The events are easier to contrast. Will Lockett was electrocuted a month after his trial, while George Floyd never received even an arraignment for his alleged crime. It is positively clear that Floyd received no justice whatsoever. Though it is questioned by some today, Lockett did receive a semblance of justice particularly given the era in which those events occurred a century ago.

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice? It is fair to question whether or not it has over the past century when looking at these two specific events, though a broader picture examining Miranda and other advances in due process might still show a forward-moving bend toward justice. In 2020, we can only hope, pray, and demand justice for George Floyd, for Breonna Taylor, for David McAtee, and for so many others. Hopefully, the arc’s progress has a longer path yet to tread.

In Lexington, protests have remained peaceful. In some instances, local police have walked with protestors and taken a knee to honor the lives lost. No curfew has been imposed in Lexington. This sort of peaceful approach makes Lexington a leader among cities (though still imperfect).

In 1920, Lexington was also perceived to be a leader. Civil rights leader W.E.B. Dubois described the local and state response to the riots during the Lockett trial (and the protection of Will Lockett before and during the trial) as “The Second Battle of Lexington” referring to the opening conflict of the Revolutionary War – it was believed to be the first time in the history of the southern United States that local and state authorities had stopped a lynch mob.

When I graduated from law school, I was given a poster with the Hebrew words Tzedek tzedek tirdof. From Deuteronomy, it means “Justice! Justice! You shall pursue!” It is my prayer that we, as a nation, will pursue (and truly achieve) justice.

This post contains excerpts from Peter Brackney’s The Murder of Geneva Hardman and Lexington’s Mob Riot of 1920 (The History Press, Charleston, SC: 2020).

For more information about the book or to schedule an event with the author, click here.

The featured image was taken during the Lexington protests on Tuesday, June 2. On the right is the Fayette County Courthouse where Will Lockett was tried.